Interest rates are more important than they have ever been

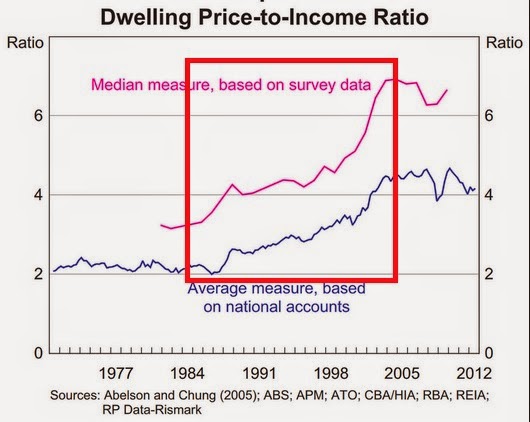

Dwelling price-to-income ratio charts in Australia and in certain other developed countries have shown a dramatic run-up which have benefited existing owners tremendously, particularly over the past couple of decades.

Most of the causes are obvious enough and have been well documented: there are now many more dual income households than there were previously, there has been and remains an ongoing colossal boom in Australia's population, there has been a structural shift to much lower inflation and interest rates, and so on.

Ultimately, though, all this new debt had to come from somewhere, so how on earth did that happen? The quick and dirty answer lies in the deregulation of the Aussie financial system which took place in the 1980s, a process often alluded to, but less often explained. A quick look at eight key points...

Regulation

During the 1980s Australian banking went relatively quickly from being one of the most stringently controlled systems in the world to one of the least controlled, as part of a wider movement which was to some extent reflected in other countries.

Crucially, Australia had previously employed very strict controls on its bank borrowing and lending practices, with few available substitutes to the traditional banks.

Normally such sweeping industry changes as occurred in that decade would be a pain-inducing and drawn-out exercise, but deregulation was especially swift and effective Down Under because it met with so little resistance from the banks themselves.

This was because the banks saw that although they may have previously benefited from the controls as they carved up housing market loans, they would now stand to benefit more from deregulation since it would allow them to compete more readily with the non-financial institutions.

With the rise of technology and electronic banking, the banks also knew that they had to become more flexible to compete with the non-banks.

The challenges with the pre-existing controls

One of the problems facing the banks was that with there being a ceiling imposed on interest rates they could lend at and on term deposits, in times of high inflation it was exceptionally difficult for them to tempt customers to deposit funds with them (and further, banks offered zero percent interest on current accounts, largely as part of an informal or unspoken cartel agreement between themselves).

With a below market ceiling on lending rates imposed upon the banks, there was in any case little willingness or indeed capability to offer more appealing interest rates on term deposits.

Meanwhile, non-bank financial intermediaries such as building societies began to offer more tempting and competitive deposit rates, which in turn facilitated the ability to lend more. With deregulation, there came too an increase in the velocity of the circulation of funds, which in turn led to an increased focus on the control of monetary aggregates by the central bank.

Government controls over housing finance changed

In the 1980s there was an imposed ceiling on lending rates for housing but this was changed in 1986. From April 1986, while a ceiling remained in place for pre-existing loans (the interest rate cap was set at 13.5% at that time, for the record), new loans written had no such ceiling.

Since new loans were written at about the same level for some time thereafter, there was initially little effect, but eventually the removal of controls did have an impact.

The traditional distinction between savings banks and trading banks was removed in 1989 and prior to that, in the mid 1980s, 15 foreign banks were given licences to operate in the Australian market. The major change in market was that a number of building societies and credit unions converted to banks.

Becoming a bank allowed these institutions a much greater capacity to expand their capital base, and from the early 1990s forth, a number of factors contributed to the banking system shifting its focus from lending to business towards housing.

Summarily, a lot of bank loans to businesses became impaired during the 1990s recession, so lending for housing got the green light. With reduced assets ratios also now required by the banks, it was time for the banks to get lending on homes...and how.

Between 1991 and 1995 the share of banks' business loans fell from 63% to 48%, but the share of loans for housing soared from 30% to 46%. Lower inflation, falling interest rates and the strong performance of housing loans saw the percentage of housing loans roar up to nearly 60% by 2010.

Why bother control housing finance at all?

Why would a government even have tried to control housing finance rates in the first place? It's a very valid question!

There is no strong economic argument in favour of such a strategy, but the basic idea I suppose to was to incentivise folk to divert more of there resources towards housing than they may otherwise have been inclined to do.

Personally, I generally prefer free markets all things being equal, but I guess at least part of the underlying notion was that if people invested more heavily in housing, them in turn the housing stock would be of better quality.

As someone born in a city with some of the worst housing developments imaginable, I can see there is some logic buried deep in there somewhere - slums and infested housing estates can create far deeper social problems than just unsightly dwellings, but what about...

Market distortions?

However, the flaws in the logic of the borrowing rate cap were equally apparent. The government was encouraging people to allocate increasingly disproportionate amounts of their resources towards housing, pushing up prices, squeezing out lower income earners, and so on.

A far better idea, one would have thought, would have been a form of subsidies for the construction of dwellings and for those who rented them - not only a clear benefit for those able to purchase dwellings through borrowing (even cash buyers were excluded from this benefit).

A ceiling or cap on housing finance interest rates generally benefits higher salary earners with clean credit histories and the ability to save deposits, with no such benefit to lower income earners who could only afford to rent. And let's face it, if a bank is forced to lend at a capped interest rate, it's going to do so preferentially to persons with a higher salary and a bigger deposit.

Combining a ceiling on housing loans with a ceiling on deposit rates (which themselves were effectively anyway capped by the below market rates accrued from housing loans) tends to hit up lower income earners with a double whammy: paying them crappy rates of interest on their savings (on average most lower income earners hold a higher percentage of their net worth in savings) and squeezing them out of the housing market.

This leads on to a whole other debate about the most appropriate form of housing subsidies for lower income groups...but that's one for another day.

Impacts of the 1986 deregulation

So in 1986 the control over interest rates was removed for new loans, but the cap remained in place for existing loans. The impact of this was a tad confusing!

Older borrowers now benefited from lower rates since they had arranged loans before 1986, although on average the older they were the lower the outstanding mortgage balance, so perhaps you could argue the outcomes of that came out in the wash a little.

And the deregulation also distorted the market in another way, making the labour market more immobile. There was very little incentive for existing owners to move to a location which might be more convenient for employment, since they would lose their entitlement to an interest rate cap upon inception of any new housing loan.

Other encouragement for housing finance

Therefore, as banks became able to offer more competitive rates on deposits, in turn this allowed them to increase their loan books.

It was expected that there would be another change from deregulation: stability. Why? Because before deregulation, when interest rates were rising banks became less competitive on deposit rates thus throttling their lending capability, yet when rates were falling exactly the opposite was true.

But what actually happened was that this great uncertainty for banks was removed by deregulation, giving them far greater control over their level of competitiveness on deposit rates in order to attract business, and thus this made them equivalently far readier to provide housing finance.

Indeed, you could argue that it now became a race to allocate as much of the new lending as possible to the housing markets.

Product innovation

Another enduring impact of deregulation was that new products sprang up all over the shop such as variable repayment loans or so-called "low-start" mortgages. Banks became more inclined to focus on the ability of borrowers to repay monthly payments rather than capping loans at a low multiple.

There was product innovation aplenty in the Aussie mortgage market as lenders sought to cater for a wider range of potential borrowers and found new ways to assess their borrowing capacity - an easing in lending standards played its part of course, increasing loan risk, but the over-arching effect was that households had wider access to credit.

With no ceiling on lending rates, banks were now able to charge higher spreads and require bigger deposits on riskier loans, so in due course became more inclined to take them on.

And then of course lenders introduced what the Americans called HELOCS - home-equity loans,as well as redraw facilities and reverse mortgages, all of which allowed households to borrow against the equity they had built up in their place of residence.

Lenders also introduced interest-only loans and shared-equity loans which made it easier for households, particularly first home buyers to purchase their home. When interest rates fell, the net result was a borrowing bonanza, and not only in Australia.

Interest rates are now more important

Pundits like to argue that in theory interest rates have little impact on housing markets, but due to the deregulation of the Aussie financial system and higher household debt today, this is incorrect, as partly evidenced by the impact of rate cuts since 2010.

What is explained above should clarify why shifts in interest rates were formerly somewhat limited in their ability to impact housing markets - since both lending and deposit rates were strictly controlled - yet today the availability and expectations around the cost of capital can be a key driver of market sentiment.

Moreover, since household debt levels are so much more elevated today than they were in the 1970s, the scope for monetary policy and adjustments in interest rates to stimulate or clobber housing markets - and indeed other parts of the Aussie economy - is greater than it was before.

Conclusion

This is all worth remembering when the next round of chart packs rolls around dating back to the mid-1800s which apparently prove that dwelling price multiples will inevitably revert to a long-term median.

They prove nothing of the sort, since credit markets have evolved beyond all recognition in the last 30 years. Unless, that is, you are expecting banks willingly to slice their percentage of lending for housing in half back to less than a third their loan books.

It strikes me that if you want to see house prices back at the oft-quoted "three times incomes", you'd need some kind of trigger. One such trigger could be a severe recession with very high unemployment.

It's simply way too easy for employed, dual-income couples in the current environment to service mortgage repayments with rock bottom borrowing rates. If you really want to see a downward reversion in dwelling prices, then we need to see higher interest rates which would quickly remove the speculative heat from the market.

You can visit AllenWargent property buyers (London, Sydney) or Pete's blog.

His new book 'Four Green Houses and a Red Hotel' is out now.