The yield curve and the RBA cash rate: Secret Agent Bulletin

GUEST OBSERVER

Bond yields are an important tool for making inferences about monetary policy. A yield curve is made by plotting the interest rates of bonds against their maturity dates. A normal yield curve occurs when long-term rates are higher than short- term rates.

This is important for an economy’s liquidity, as banks can make a profit by borrowing at the (lower) short-term rates and lending at (higher) long-term rates.

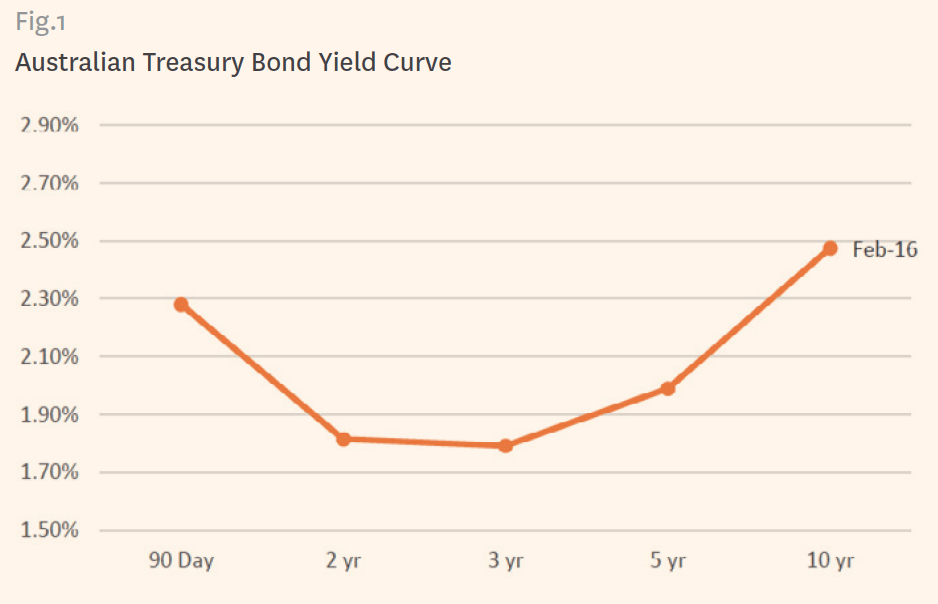

Figure 1 shows the current yield curve on Australian Treasury bonds with maturities between 90 days and 10 years. Parts of the yield curve are inverted, meaning short-term rates (90 days) are higher than some long-term rates (2, 3 and 5 years). This creates a disincentive for banks to lend and if the entire curve is inverted, it can lead to a “credit crunch”. This happened in the US during the global financial crisis, when money suddenly dried up because banks could no longer profit from lending out money.

To avoid a credit crunch, either long-term rates need to rise, or short-term rates need to fall. The first option is tied to investor expectations, as the yield on 10 year bonds is usually an indicator of peoples’ outlook for the future of the economy. This is hard to change. The relatively easier option is lowering the short-term cash rate, otherwise known as Quantitative Easing.

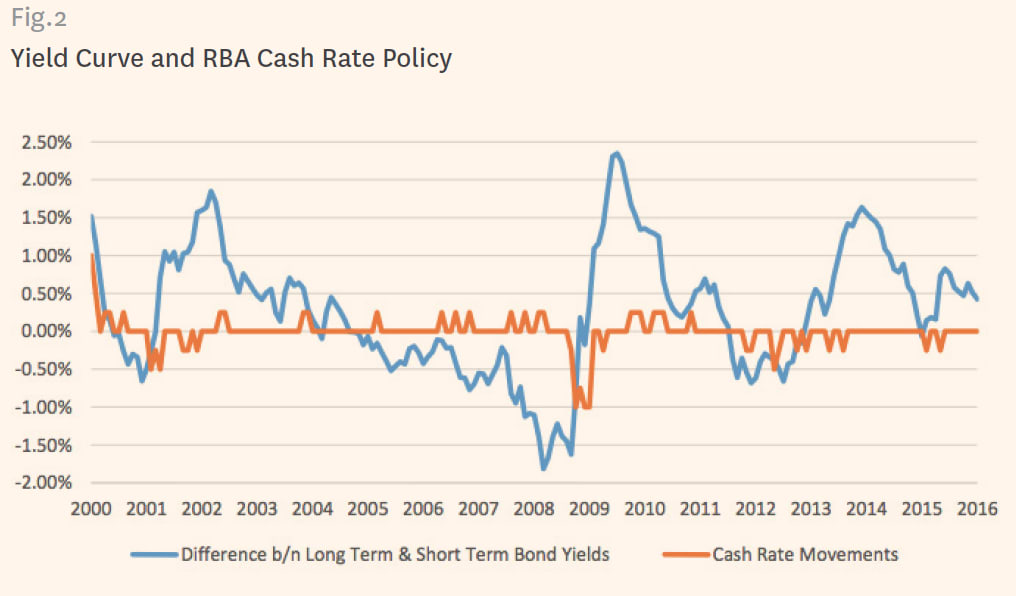

Figure 2 compares movements in the yield curve (Figure 1) and the RBA’s cash rate target. The blue line shows the difference between 10-year Treasury bonds and 90-day Treasury notes for any given month. If the line is above zero, the yield curve slopes upward, while if it is below zero, the yield curve is fully inverted. The red line shows movements in the cash rate: if it is on zero, the cash rate stayed the same that month, while if it goes up or down, there was a change in the cash rate. Notice that for the whole timeline (Jan 2000 – Jan 2016) interest rate cuts always followed an inversion of the yield curve.

When the bond yield curve inverts, intervention is often necessary to keep the economy stable and allow banks to keep lending out money. However, cutting interest rates is a blunt tool as it has ripple effects on the economy including increased demand for housing loans, a devaluation in the Aussie dollar, which in turn changes trade balances and so on. With an already highly inflated housing market and worries about a bubble, the RBA is often reluctant to cut the cash rate if it is not absolutely required.

Will interest rates change in then ear future? With a positive yield curve it may seem unlikely there will be another cut. However, the difference between yields on 10-year bonds and short-term debt is at only 0.4 percent and has been falling since the last interest rate cuts in 2015.

Notice that when the bond yield curve is falling, the trend continues until interest rates are cut. It is often dangerous to use historical patterns to predict the future, and other economic factors always need to be considered.

For more information, click here.