Chinese local government debt fears are returning: NAB's Gerard Burg

EXPERT OBSERVATION

China’s response to growing trade tensions with the United States has been multi- faceted. China’s central government has proposed loosening policy restrictions on infrastructure investment – developments that are typically managed and funded at the local government level.

The latter could be problematic, as China’s local government debt could be much larger than widely thought – an echo of earlier fears from early 2014.

COMPLEXITY OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT DEBT MAKES IT HARD TO ASSESS

China’s local government debt levels are at best opaque. According to official data, the total debt of local governments – which comprise a broad range of authorities at provincial, city, county and village/town level – was RMB 18.3 trillion in September 2018, equivalent to around 21% of GDP.

However, it is likely that this figure does not present the full picture of their debts – which are larger, more complex and risky.

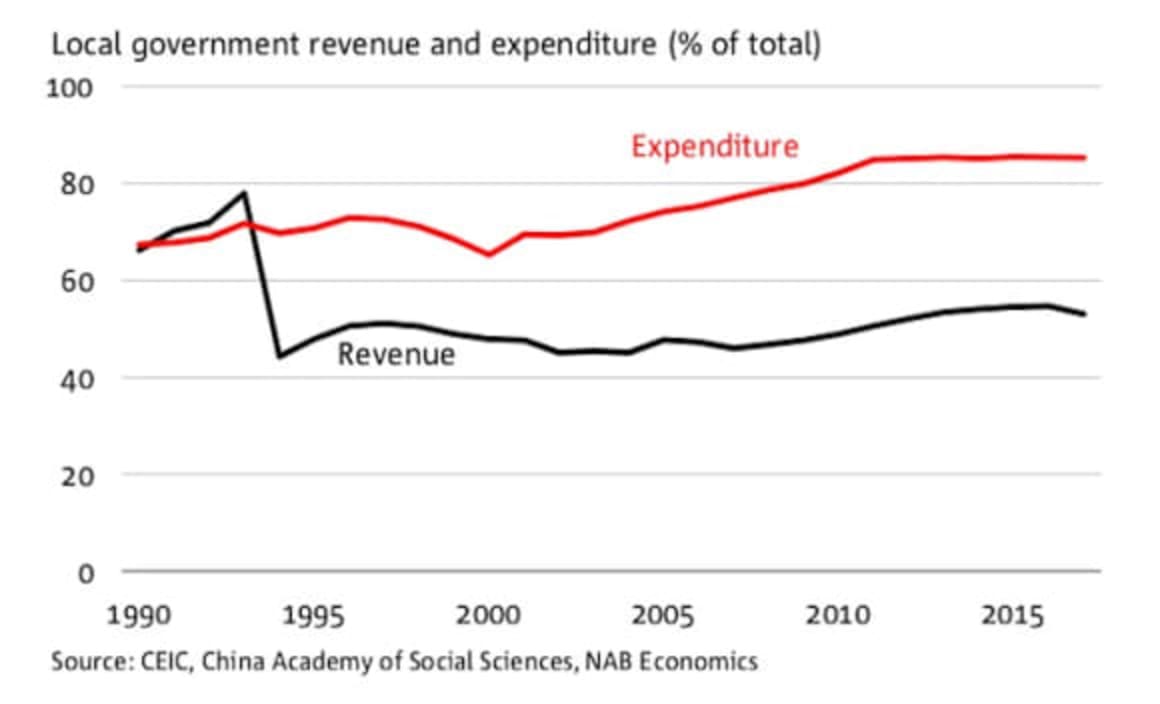

CHINA’S BUDGET IMBALANCE

Local governments struggle to fund their spending.

Following the 1994 Budget Law, which shifted much of the revenue generation from local governments to Beijing, local governments were forced to generate alternative sources of funding to meet their expenditure requirements. The local government share of fiscal revenue fell from 78% in 1993 to 44% in 1994. Prohibited by this law from issuing bonds or borrowing directly from financial institutions, they established local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) – which secured debt from banks, shadow banks and other sources.

The scale of this debt expanded rapidly in the post-GFC period, as China’s infrastructure program spared the country from the worst of the crisis.

At the end of 2013, China’s National Audit Office released a detailed review of local government debt – highlighting the broader scale of these liabilities. In addition to the debts that local governments had direct obligations to repay (around RMB 10.9 trillion in mid-2013) – which matched the official debt statistics above – these authorities also had hidden debts (including those debts they guaranteed for LGFVs or public-private partnerships) – which totalled an additional RMB 7.0 trillion. However, this broader estimate of local government debt has not been updated since late 2014.

Fears around this debt largely dissipated since this period, in part because Beijing permitted provincial, municipal and some city governments the authority to issue bonds from mid-2014 (subject to annual caps). Ministry of Finance data suggests that bonds accounted for almost 90% of the reported total debt at the end of 2017.

However, the bulk of bond purchasers have been banks – at the behest of the central government and regulators – with the returns on these bonds usually unattractive to other investors. Overall, the lower level of concern appears due to hidden debt being overlooked, rather than it being effectively addressed.

In late March 2018, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences estimated that the total off-balance sheet liabilities of LGFVs was in the order of RMB 30 trillion, while a further RMB 10 trillion could be hidden within so-called public-private partnerships (where the “private” partner has often been a state-owned enterprise).

A recent report by Standard and Poor’s produced a similar range for off-balance sheet debts. These estimates are relatively uncertain, since the sheer number and complexity of LGFV arrangements makes them difficult to track.

OFF-BALANCE SHEET DEBT

Growth largely overlooked since 2014

Combining these estimates of off-balance sheet debts to the officially reported sums suggests that China’s local government debt could be in the range of 55% to 66% of GDP in September 2018. With another 16% of GDP in central government debt, this suggests that China’s total government debt is well above the 60% benchmark that is seen as a prudent limit in advanced economies. It is also above the IMF’s estimate of China’s total government debt – which was around 47% of GDP in 2017.

DEBT RISKS RISING IN CURRENT CLIMATE

A critical problem related to China’s local government debt is the capacity of these authorities to service these liabilities. The total fiscal revenue of local governments was just RMB 9.1 trillion in 2017 (less than one-fifth of the lower bound estimate of total debt).

With limited ability to collect tax revenue (following the 1994 law change), many local governments have relied on land sales as a key source of income – averaging around 32% of the total in 2017 (behind central government transfers) – albeit the share differs widely across the country.

Land sales are not considered a sustainable long term of revenue, and a fall in sales could result in local governments defaulting on their debts or failing to support distressed LGFVs. This could flow into greater instability in China’s financial sector, particularly if central authorities follow through on public statements and do not provide a bail out.

LOCAL GOVERNMENT REVENUE (2017)

Land sales contribute too much to funding

Similarly, increasing infrastructure investment in the short term could mean a large expansion in local government debt, leading to higher interest payments even if revenue levels can be maintained. The mismatch between the short term maturity of many sources of local government debt – such as bank loans and shadow banking products – and longer term return on infrastructure investment leads to greater risk.

CONCLUSIONS

The greater scale of local government debt than is widely acknowledged in official figures highlights the risks associated with infrastructure led stimulus to China’s economy. It also highlights the need to continue reforms to the broader economy – where progress has been disappointing. A key reform that would boost the sustainability of local government revenues would be the implementation of property taxes – proposed for over a decade, but repeatedly delayed. A nationwide tax had been scheduled for introduction in 2019, however this proposal has been delayed with an uncertain start date.

GERARD BURG is senior economist - Asia Group Economics at National Australia Bank.