China's property sector slowing amid growing fears of overheated market: NAB's Gerard Burg

GUEST OBSERVER

The real estate sector has been a key driver of China’s economic growth in recent years, helping to support the economy during the transition away from growth led by investment in heavy industry towards domestic consumption.

However, this growth has also built a sizeable debt burden which will have to be carefully managed in coming years to avoid a major downturn.

This is the first of two parts looking into the real estate sector. This part provides a high level view of the importance of the sector and recent trends, while part two will look at the risks related to the sector going forward.

PROPERTY SECTOR A CORE COMPONENT OF CHINA’S ECONOMY

Private ownership of real estate has a short history in China. Prior to the period of opening up that commenced in 1978, all property was state-owned. Two decades of gradual reforms saw the introduction of ‘commodity houses’ in 1998 – private properties that could be bought and sold at market prices. Chinese residents embraced home ownership – with surveys conducted by Peking University showing that around 90% of households own their home.

The property sector is a critical part of China’s economy, and has been a major driver of growth over the past decade. In 2017, the broad sector (accounting for construction and real estate services) comprised 13.2% of China’s economy – compared with 10.8% a decade earlier, highlighting above average growth over this period. The IMF estimates that when combined with upstream and downstream demand (including cement and steel, along with furniture, electronics and automobiles), real estate drives around a quarter of the Chinese economy.

Similarly, investment in real estate (as a share of GDP) rose sharply from the start of the century – peaking at almost 15% of GDP in 2014, before easing back to 13.3% in 2017. The residential sector accounts for over two-thirds of this total. The trend over this period was supported by the mass migration of Chinese residents from rural areas to cities, as well as a substantial improvement in the quality of housing for existing urban residents.

Property a major part of the economy

Real estate’s importance to the financial sector has also increased in recent years. Outstanding loans to real estate have rapidly increased over the past decade – from around RMB 4.8 trillion to over RMB 32 trillion in Q4 2017. This increase has outpaced lending growth to other sectors as well as the broader economy– with real estate lending (as a percentage of GDP) increasing from 18% a decade ago to around 39% at the end of last year. Although this share is not particularly high when compared with advanced economies – particularly Australia (where it is around 90% of GDP) and the United States – its rapid growth poses some concern.

The key contributor to the increase in real estate lending has been residential mortgages – with the mortgage share of total real estate lending rising to 74% in December 2017, up from 63% in December 2007. In addition, the property sector has lured funds from the shadow banking sector (although data on this sector is patchy at best). In Q3 2017, around 10% of funds from the trust sector (one component of shadow banking) were invested in real estate.

Property loans have grown rapidly

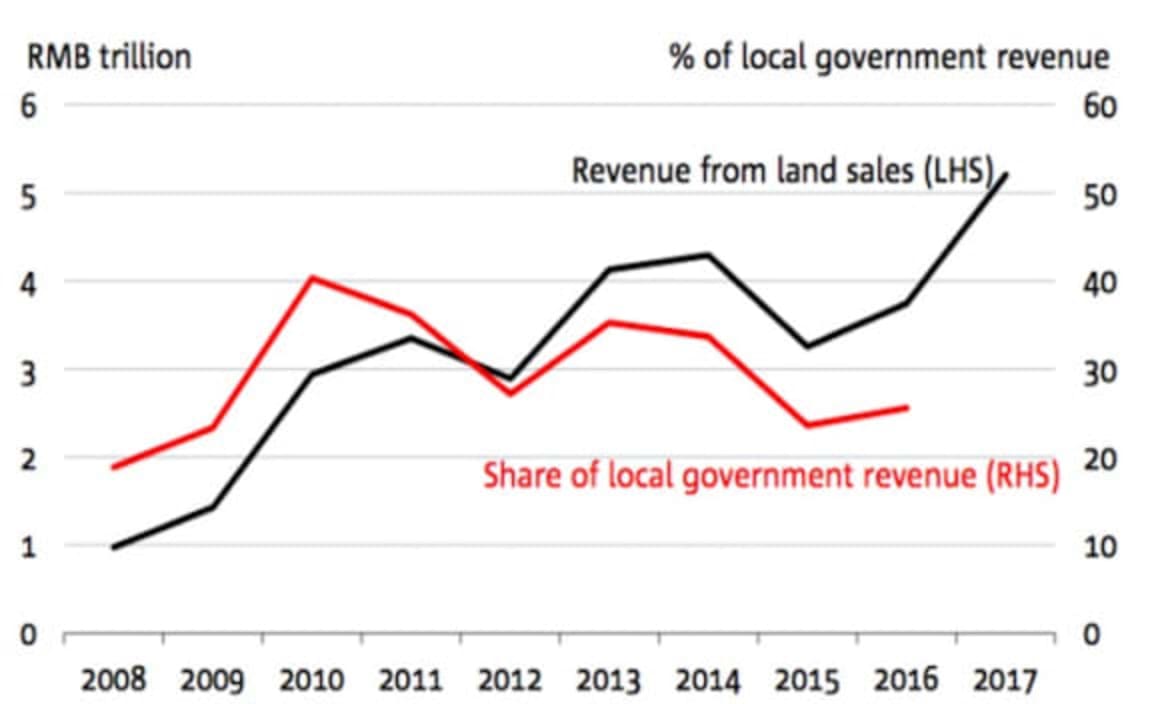

Finally, the sector has been extremely important to government balance sheets – with land sales a major source of revenue for the often highly indebted local governments. In 2016, land sales accounted for almost 26% of the total – although this share varies widely across the country. Governments also benefit from tax revenue from the real estate sector – although at present there are no residential property taxes. The sector is also been a major employer – around 27 million people were employed in construction in 2016, with a further 4 million in real estate management, which together accounts for almost 18% of urban employment (and with it income tax revenue).

Land sales still a major source of funding

This implies that there are various bodies – both state and private – that benefit from continued growth in construction and property development, despite growing concerns around oversupply once again. This incentive to continue to expand increases risks around China’s economy.

RECENT TRENDS IN PROPERTY

China’s previous residential property cycle peaked in April 2014 – following a period of domestic and international concern around potential price bubbles and overbuilding (particularly in so-called ghost cities). Aggregate prices for 70 major cities fell over the next twelve months before the recovery commenced (led by the largest Tier 1 cities – Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou).

During this period, there was a substantial slowdown in investment in the real estate sector – with the rate of growth down from around 15% yoy (on a three month moving average basis) to -0.6% yoy (3mma) by November 2015. This resulted in a drop in construction activity, with residential starts (measured in square metres of floor space) falling considerably between February 2014 and January 2016. These weaker conditions flowed through into the next link in the chain – local government revenues from land sales fell 24% in 2015 on weaker demand from developers.

PROPERTY PRICES BY TIER - Vast disparities between China’s cities

However, investment in real estate recovered in 2016 – as easing property purchase restrictions allied to a credit boom, fiscal stimulus and poor performance in other asset classes supported a fresh surge in property demand and construction activity. Much of the attention was focussed on the extraordinary price increases in tier 1 cities – by September 2016, prices in these locations were 40% above their April 2014 peak – however these cities accounted for just 8% of real estate investment in 2016 (IMF). The majority of investment (59%) occurred in smaller tier 3 and 4 cities (where prices in December 2017 were only 4.0% above the previous peak), where concerns around oversupply have been higher.

This growth provided a major boost to China’s economy in 2016 – at a time where fears of a hard landing were elevated. In real terms, real estate and construction grew by 8.6% and 7.2% respectively in 2016, well above the rest of the economy.

Growing fears around overheating property markets have seen a tightening in property policies since this time– including higher down payments, restrictions on finance and tighter eligibility for purchases – however these policies have varied across the country. Prices stabilised in tier 1 cities and growth slowed substantially in tier 2 ones. As a result, the strong growth in construction starts and property sales in the first half of 2017 slowed considerably in the second half.

CONCLUSIONS

We anticipate the slowing trends generally exhibited across the property sector in late 2017 will extend into this year. Slowing sales and softer price trends should flow through into weaker construction activity – which would have downstream effects for steel and cement demand (along with Australian iron ore) and local government revenues (with land sales likely to fall as well).

Gerard Burg is senior economist - Asia Group Economics at National Australia Bank.