The property market dynamics influencing affordability

Affordability

While on the face of it the level of housing affordability is what causes our housing markets to ebb and flow, it's as likely to be the unemployment rate and the availability or otherwise of credit in Australia which drives property market movements.

The unemployment rate currently sits at a historically low level at under 6%, but has been rising moderately through 2013.

The issue of affordability is an ongoing one, and being an emotive issue, sometimes the dynamics of how housing markets actually work in practice are overlooked.

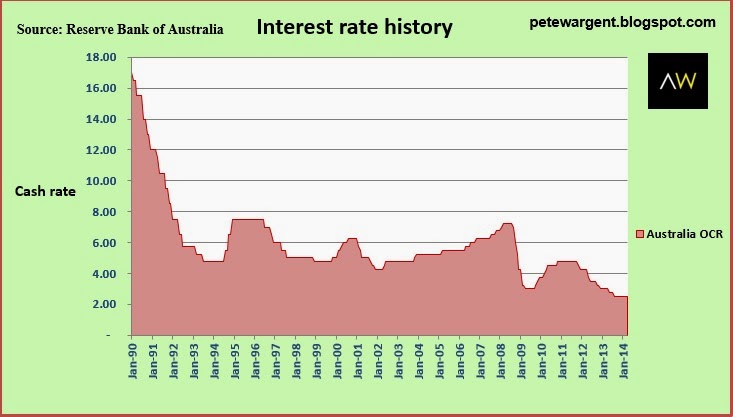

The great paradox of today's rising asset prices is that the prevailing low interest rate environment has improved affordability considerably for existing home owners, but made life correspondingly worse for first time buyers as entry prices to the market rise.

Older clients often come to me expressing surprise at the level of their surplus income, the driver of which has clearly been the structural shift to low inflation and lower interest rates over the past 25 years.

Multiples of income

The way in which housing markets from different countries are compared to each other is most often by taking the median price of a house and dividing it by an average measure of household incomes to produce a multiple.

Looking at how long it would take to pay off an average house with an average income is a handy shortcut measure of housing affordability and a very easy means of comparison, but this isn't how housing markets work in reality since it flatly ignores the role of interest rates and the differing financial situations and stages of life that buyers of property are in.

This widely favoured methodology fails to consider mortgage repayments - a housing market where prices are a low multiple of incomes yet has mortgage rates approaching 20% may still not necessarily be an affordable market.In other words, the multiple of incomes method works on the presumption that everyone is a first home buyer with a 80-100% loan.

In the real world, our housing markets work very differently.

There are essentially four different types of buyer, and issues of affordability affect each of them differently.

- No finance

The percentages fluctuate each year and by state, but between a quarter and a third of properties tend to be bought with no financing.

How so?

Well, there are some lucky so-and-sos whose parents buy their homes for them, but most often this happens due to the sale of an existing home. Empty-nesters and down-sizers form part of this phenomenon.

Other older buyers who are mortgage free opt to move to a similarly-sized home and thus require no debt financing.

By the end of 2013, the total of all Australian household debt reached a record $1.84 trillion as the population expands.

Yet even the sum total of all forms of household debt is comfortably dwarfed by the value of housing assets as estimated by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (click chart):

Cash buyers are affected little by rising interest rates and often they remain unaffected by the base value of housing, since the asset which they are selling may rise in tandem with the asset they opt to buy. - Investors

As our capital city housing markets mature and the population expands largely by immigration, it is expected that the number of properties owned by investors will also increase.

In cities such as Sydney around half of loans presently written are investment loans, but Australia-wide one of the gauges over time of how much property is bought by investors is the rate of home ownership, which also seems likely to slide in the decades ahead.

Since some investors choose to own multiple properties, investors tend to comprise around a quarter of buyers.

Affordability is not really an issue for most investors in the low interest rate environment, since rental income pays the bulk (if not all) of the mortgage and there are tax deductions available for on-paper losses.

Investors instead elect to buy at times when rental yields are acceptable as compared to other available investments and in regions where they expect to see capital growth.

Most property investors are looking for locations where the population is expected to grow over time and therefore they are very heavily focused on capital cities and larger regional cities. - Existing mortgagors

Again, the percentages fluctuate each year and by state, but around a third of the market of property buyers are existing mortgagors who have equity in their home.

So the issue for these buyers of affordability is largely governed by interest rates and the price gap between the property they own and the one which they want to own.

Note therefore, that housing affordability for these buyers is correspondingly unrelated to the base value of their existing property, and is instead much driven by their own aspirations. - First home buyers

The remaining 10% or so of property buyers are first homebuyers, which is the one sector of the market for whom repayments versus household income is a genuinely worthwhile measure.

For this sector of the market the challenges to be overcome include the deposit gap and whether mortgage repayments can be well covered in the event of future interest rate hikes.

The first homebuyer demographic which has access to a deposit and mortgage finance is driven by another equation: the cost of renting versus the expected mortgage repayments if a home is purchased.

This article continues on the next page. Please click below.

Granularity

The above dynamics help to explain why US forecasters who predicted an Australian property crash have not to date seen their expected outcome.

A multiple of income measure is one measure of housing affordability, but in itself doesn't guarantee a price correction where a strongly rising demand is exceeding supply

This is particularly so where most of the population remains employed.

The above dynamics show that perhaps around 90% of buyers are not impacted by affordability in the manner which commentators frequently imply.

This is where the point on granularity comes in.

House prices in London have been able to run up to outrageous levels and by another 20% or so in the past year alone since there is a woefully low level of ongoing dwelling construction but demand is rising.

Yet in the north-east of England, more than 50% of first homebuyers who bought homes in 2007 remain in negative equity even seven years on.

The difference in outcomes is due to the respective supply/demand imbalances.

While it's certainly useful to compare price to income multiples to a point, it would be unwise to expect all markets to behave in the same manner in this regard.

In the case of parts of New South Wales, there exists a genuine challenge for the rising demand of the coming decades to met by quality supply.

Here is how things stand in Sydney's inner suburbs at the moment, which is to say, verging on crisis levels.

Clearly certain regional markets do not face anything like the same issues, especially as population growth in New South Wales is tracking below the national average in almost every regional town as I considered here.

Since we don't face the same demographic challenges in Australia as some other European countries where dependency rates have increased alarmingly, far more important will be how our economy progresses and the extent to which credit markets remain liquid and mortgage financing remains so widely available.

Further, while most of the value in housing market is equity rather than debt, and while a third of property is owned debt free (and a growing percentage by investors) those who are hurt financially by softer periods in the housing markets are likely to be those who are forced sellers such as the longer-term unemployed, those who have to relocate for employment, divorcees and deceased estates.

Other potential vendors have the luxury to 'wait out' softer periods in the market and as such are less likely to experience an adverse outcome.

Warning - the popular media is late to the party and tipping Erskineville as a hot suburb, which means that you've long missed the time to buy.

As we said here previously, the time to buy in Erskineville was 2007/8 when it was still seen to be a less attractive proposition - and as we anticipated, apartment prices in the suburb have risen by 56% in the last five years.

It's time to look elsewhere.

Sources: I've leaned heavily here on the ideas of John Lindemann and his work in the Mastering the Australian Housing Market (Wrightbooks, Queensland, 2011).

You can visit AllenWargent property buyers (London, Sydney) or Pete's blog.

His new book 'Four Green Houses and a Red Hotel' is out now.