Solid gap between business and consumer sentiment: Gareth Aird

GUEST OBSERVER

Does the falling household saving ratio help to reconcile the disparity in consumer and business confidence?

A solid gap has opened up between business and consumer sentiment. A falling saving ratio, which has supported household consumption in the face of declining wages growth, looks to be one of the important factors contributing to the disparity in confidence. It may also help to explain why investment growth is soft despite strong business conditions and confidence.

Overview

Confidence can be a powerful force. The sentiment of households and businesses regularly plays a role in shaping economic activity. Economists and policymakers often look at measures of reported confidence as forward looking indicators of consumption and investment. Right now, however, the surveys of business and consumer sentiment are sending conflicting signals.

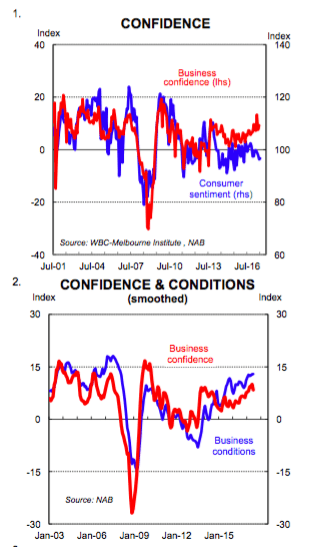

A solid gap has opened up between business confidence (and conditions) and consumer sentiment (chart 1). The NAB business survey suggests that business conditions are at their highest level since 2008 while confidence is at an above- average level. In stark contrast, the WBC/MI consumer sentiment report indicates that household confidence is fragile.

In the past, there have been disparities in how consumers and businesses feel. But these divergences tend to be ‘ironed out’ over time and the results converge. This time around the disparity has persisted for an unusually long time.

In this note we attempt to reconcile why business confidence has been so buoyant despite consumers feeling downbeat. On the surface it’s easy to understand why consumers don’t feel good.

Real wages have fallen, household income growth is weak, debt levels are high and the labour market still has plenty of slack in it. As we covered last week, per capita measures of the economy suggest that there hasn’t been a lot a joy for households since the downturn of the mining investment boom.

We won’t go through the details again in this note other than to say that there is nothing unusual in the persistently weak monthly readings of consumer confidence. But what looks surprising, at least on the surface, is the reported high levels of business confidence. After all, non- exporting industries are selling goods and services to domestic households. And generally speaking, pessimistic consumers are bad for businesses because they reign in spending.

We postulate that a falling saving rate, which has supported consumer spending, has helped to prop up business confidence and profits despite the household sector feeling gloomy and doing it tough. If we are right then the disparity can only persist until the saving rate hits a floor. At which point business confidence is likely to soften without a lift in household income growth.

Why is business confidence high?

The two headline figures in the NAB Survey that relate to business conditions and confidence have posted strong outcomes in 2017 (chart 2). Business conditions hit a post-GFC high in June. And business confidence, which was a little softer, came in well above its long-run average level. According to the survey, there’s broad-based strength in the numbers because most industries have been performing well.

Some of the recent “hard” data helps to explain why businesses have had a much

better time than consumers of late. The big lift in national income over the past year has largely been confined to the corporate sector as profits rather than spilling over to employee wages and salaries.

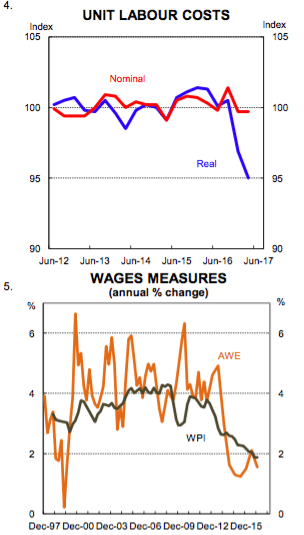

And unit labour costs are low because wage growth is weak (chart 4). This has kept a lid on the single biggest operating cost that businesses face.

Growth in labour market supply has facilitated this.

Furthermore, the global economy has improved, which provides a boost to demand for Australia’s exporters. What is unusual, however, is that sales growth has been decent while the household sector struggles.

Why is consumer confidence weak?

It’s not hard to see why consumer sentiment is stuck in the pessimistic zone. Our note looking at the Australian economy on a per capita basis spoke to the heart of the matter. Namely that growth in living standards has stagnated and for some sections of the resident population, in particular younger people, it has gone backwards.

The trends in the data on wages (chart 5), real household income per person (chart 6), debt to income, and labour market spare capacity suggest that consumer pessimism is unlikely to lift in the near term. In fact, real wages growth may fall further into the red zone when the sharp lift in electricity prices finds its way into the headline CPI. This will naturally weigh on the consumer.

Can the saving rate helps to explain the disparity?

The saving patterns of households can be a big driver of economic activity. The proportion of income saved influences household consumption which is worth 57 per cent of GDP.

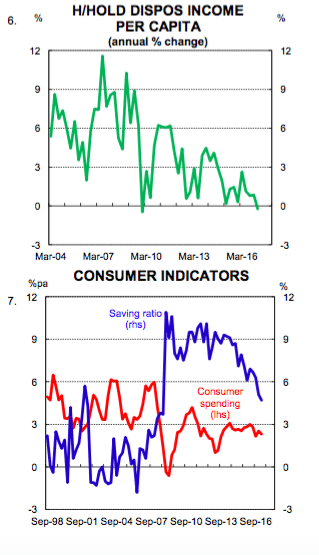

In Australia, the saving rate1 has been falling since mid- 2012. This means that expenditure growth over that period has outpaced income growth. As chart 7 shows, household consumption growth has been pretty stable in Australia despite falling wages growth because the saving rate has come down.

There are two reasons, broadly speaking, why the saving rate may fall. First, consumers may feel good about the future and their personal finances which means they feel comfortable reducing the amount of income that is saved each period.

Alternatively, the saving rate may be falling so that households can maintain a constant level of consumption in the face of declining income growth.

The evidence suggests that it is the latter situation driving the recent decline in the saving rate. We know this because over the recent past, household income growth has slowed while consumption growth has remained broadly flat. And on top of this, consumer sentiment has been mired in the pessimistic zone all year.

We can therefore infer that businesses, at an aggregate level, have benefited from falling unit labour costs but relatively constant sales growth thanks to a falling household saving rate.

That means stronger profit growth, which lifts business confidence, all else equal. In the context of the above, we now have a better insight into the disparity between consumer and business confidence.

Of course there are other factors like firmer commodity prices which have boosted resources profits. But given the broad-based strength of the NAB business survey we think that the fall in the saving rate has played an important role in explaining the disparity.

What does it mean for the outlook

If the savings rate stops falling, and it must hit a floor at some point, then household income growth and consumption growth will converge. Some of the consumer pain will then be felt by the business sector unless a meaningful lift in wages growth arrives that can propel consumer spending higher.

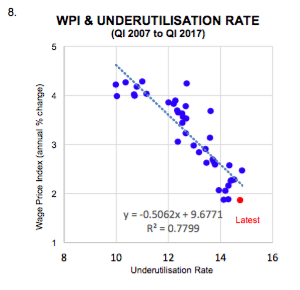

We don’t envisage that happening in the near term given the level of spare capacity in the labour market (chart 8).

Historically business confidence tends to be a good gauge of investment intentions. Higher levels of confidence are usually a precursor to a lift in capital spending. In this case, however, the strong confidence and conditions numbers have not generated a commensurate lift in investment. Again, we suspect that the consumer is playing a role here.

Many businesses will be aware that household budgets are stretched and that a falling saving rate has supported consumption. There has also been a lot of coverage recently on the level of debt that the Australian household sector is carrying.

As a result, it may be the case that expectations of future consumer demand are too low to justify a lift in investment at this point in time despite positive levels of confidence and conditions.

The upshot of this means that our monetary policy call looks more aligned with the consumer sentiment figures than what the NAB business survey is suggesting.

As such, we continue to see the RBA on hold well into 2018 despite a more optimistic tone in the July Minutes.

Gareth Aird is economist at Commonwealth Bank and can be contacted here.