There’s more to the compact city than getting dense

Melbourne’s strategic planning history has largely overlooked the contribution of Ruth and Maurie Crow.

The Crows were early champions of functional mix and compact urban development. They didn’t eulogise lower-density suburban form, but equally didn’t advocate higher densities as necessarily humanising in themselves.

In their three-volume Plan for Melbourne, published from 1969-72, the Crows argued for compact urban development driven by spatial justice ambitions. Revisiting their work provides a counterbalance to evaluate the motivations for the transformations of our cities today. Their Plan for Melbourne shows a prescient awareness of the need to design cities to maximise access and interaction:

the debate around the plan for the future of a city is not essentially a debate about things … buildings, cars, trains, roads and so on, and their placement; although it often expresses itself in these terms. It is essentially a debate about human relationships.

The Crows’ pioneering work, Plan for Melbourne, was published as three volumes in 1969, 1970 and 1972. Ruth & Maurie Crow Collection/Victoria University Library.

The compact city has been a steadfast trope in Australia’s strategic planning rhetoric since the 1980s. Consolidation of urban areas, containment of outward growth, and a multi-nuclear metropolitan structure are deemed necessary to support increasing populations in uncertain socio-ecological futures.

Despite this naturalised policy ambition, metropolitan planning has delivered what Clive Forster termed a “parallel universe phenomenon”. The vast gaps between planning intent and urban reality have everyday justice implications, resulting in a parallel justice phenomenon.

The justice ambitions have often been subsumed into transformations of our cities driven by economic rationality. For the Crows, the goal of social justice was paramount.

What has driven urban transformations?

Melbourne’s strategic planning history is marked by an alternating desire for containment and decentralisation. Various propositions have come to the fore, including “the dispersed city”, “satellite cities”, “growth corridors”, and “the redirected city”.

The late 1960s and early 1970s were a transitional moment in Melbourne’s development. Unfettered expansion had typified the city since the 1930s. Now the growth trajectories of both the metropolitan area and the central city were being publicly questioned.

The Crows’ Plan for Melbourne was rejected on the grounds of its seemingly unachievable restructuring propositions. Instead, in 1971, the Melbourne Metropolitan Board of Works advanced the elusive “growth corridors and green wedges” policy. The radical implications of the Crows’ proposed “clustering”, “concourses” and “collectives” to create an inclusive, accessible and convivial city weren’t considered.

The compact city ideal was not validated in official planning rhetoric until the 1981 strategic plan. Spatial consolidation then became de facto policy. The aim was to promote inner-city population and employment growth, as well as greater use of existing infrastructure and services.

However, market-driven compaction contributes to uneven distribution of, and precarious access to, social infrastructure, affordable housing, public transport and hospitable urban life across the city. The result is a shortfall of social justice.

Revisiting a vision of a different city

Heavily involved in citizen activism, The Crows dedicated themselves to the “urban action movement”. They were amateur planners, heterodox communists, and avid community members. They proposed radical alternatives to what they understood as the injustices of urbanisation and capitalism.

They wanted a city that was more rewarding, both socially and ecologically. This was their rallying cry:

You have to project the future: a more workable, more humane, more ecological future, and then battle towards it. Maybe the goals will change as you battle towards them: but without goals there is no battle, only unending class scrimmage within the system.

For the Crows, urban consolidation had two interlocking objectives. The first was to concentrate social activity and so minimise transport energy. The second was to heighten participatory enjoyment.

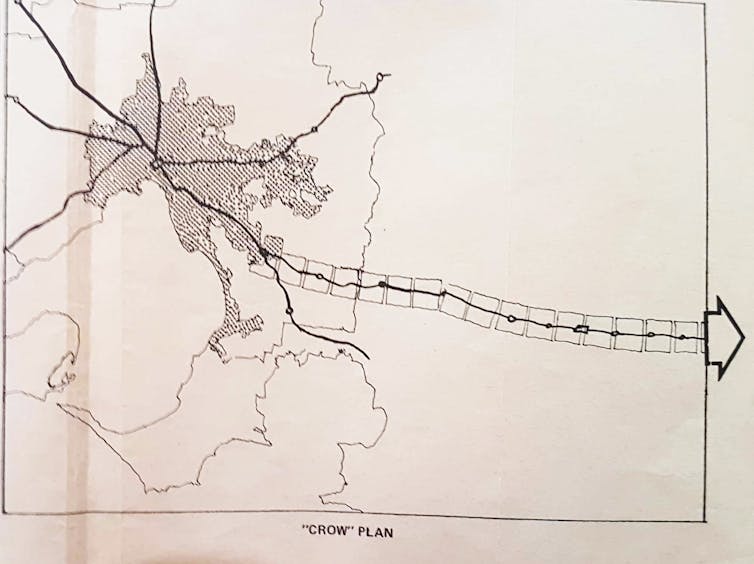

Image of the linear city from Plan for Melbourne Volume 3. Courtesy of the Ruth & Maurie Crow Collection, Victoria University Library

Clustering, concourse, collectives

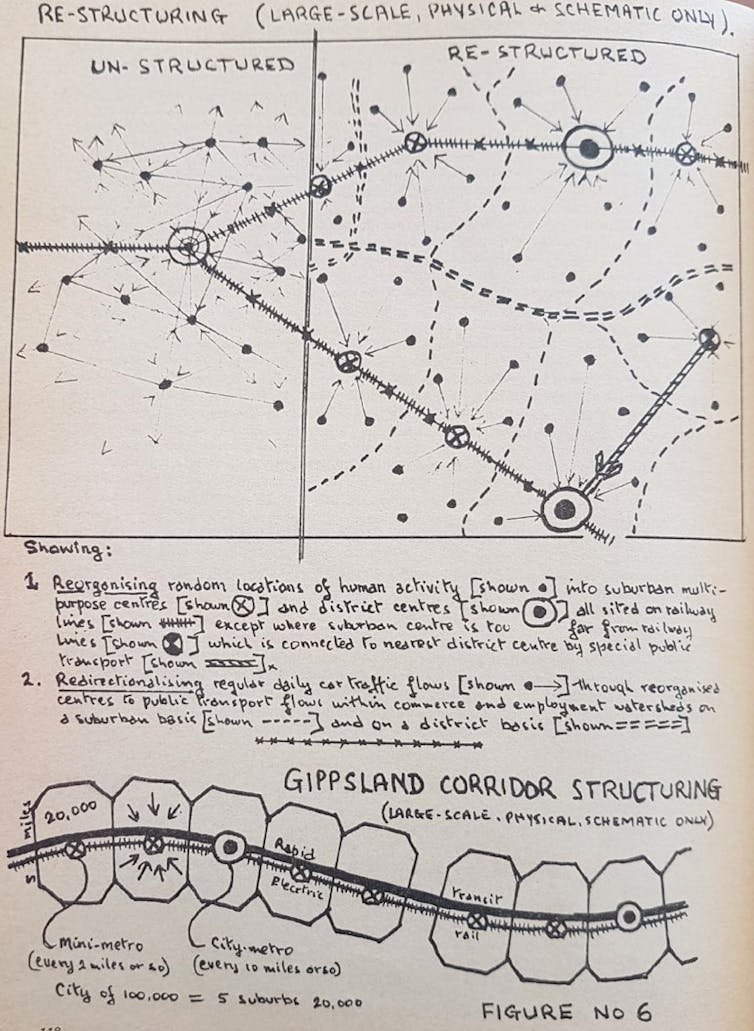

The Crows proposed a compact city with explicit structural elements. In their future Melbourne, towns were to be clustered along a linear spine towards the southeast. A rapid transit network would connect a string of “mini-metro hearts” and “city-metro hearts” to allow for easy commuting.

Multi-functional zoning and high-density cores distinguished their towns from existing suburbs. The Crows proposed dedicated first-level concourses in their “metro hearts” to promote commerce-free encounters. These high-density core areas were to be entirely vehicle-free and were intended to overcome social isolation.

Concourses were designed as a “therapeutic measure”, counteracting the “community scattering trend” of the car. These areas would allow for “deliberate voluntary contact”, encouraging interaction beyond the fleeting yet pervasive contact of commercial transaction. The Crows’ intention was to catalyse spaces for voluntary collectives to form and flourish as a means to enhance the “tone” or “ethos” of the community.

Proposed restructuring of Melbourne’s future growth, from Plan for Melbourne Volume 3. Courtesy of the Ruth & Maurie Crow Collection, Victoria University Library

Compaction for conviviality

The Crows’ Plan for Melbourne presented a radical alternative to what mainstream planners were proposing at the time.

Their calls for compaction were informed by spatial justice ambitions to minimise alienation, increase accessibility and support the need for social interaction. They proposed clustering, concourses and collectives to ensure access and inclusion; this was compaction for conviviality rather than capital accumulation.

Melbourne has certainly transformed into a vibrant centre since the Crows’ Plan for Melbourne. Whether it is being planned as a just city is questionable. Hyper-density and visible homelessness are now emblematic of the city.

![]() The Crows warned 50 years ago that, without a clear justice intent driving metropolitan development, we risked looking back with regret that the struggle to shape our cities for their citizens rather than vested interests began too late.

The Crows warned 50 years ago that, without a clear justice intent driving metropolitan development, we risked looking back with regret that the struggle to shape our cities for their citizens rather than vested interests began too late.

Claire Collie, PhD candidate in Urban Planning, University of Melbourne

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.