Is there still a housing shortage in Australia? ANZ Research says about 250,000 dwellings

The national shortage of housing in Australia is nearly 250,000 dwellings, lower than previously estimated, but still a long way from being in structural surplus, according to ANZ Research's latest Economic Insight.

The study forecasts that housing construction and underlying housing demand will see a modest unwinding of the current housing shortage in coming years. This easing will, however, challenge the short-term support to dwelling sales and price growth from the underlying supply-demand imbalance in some markets.

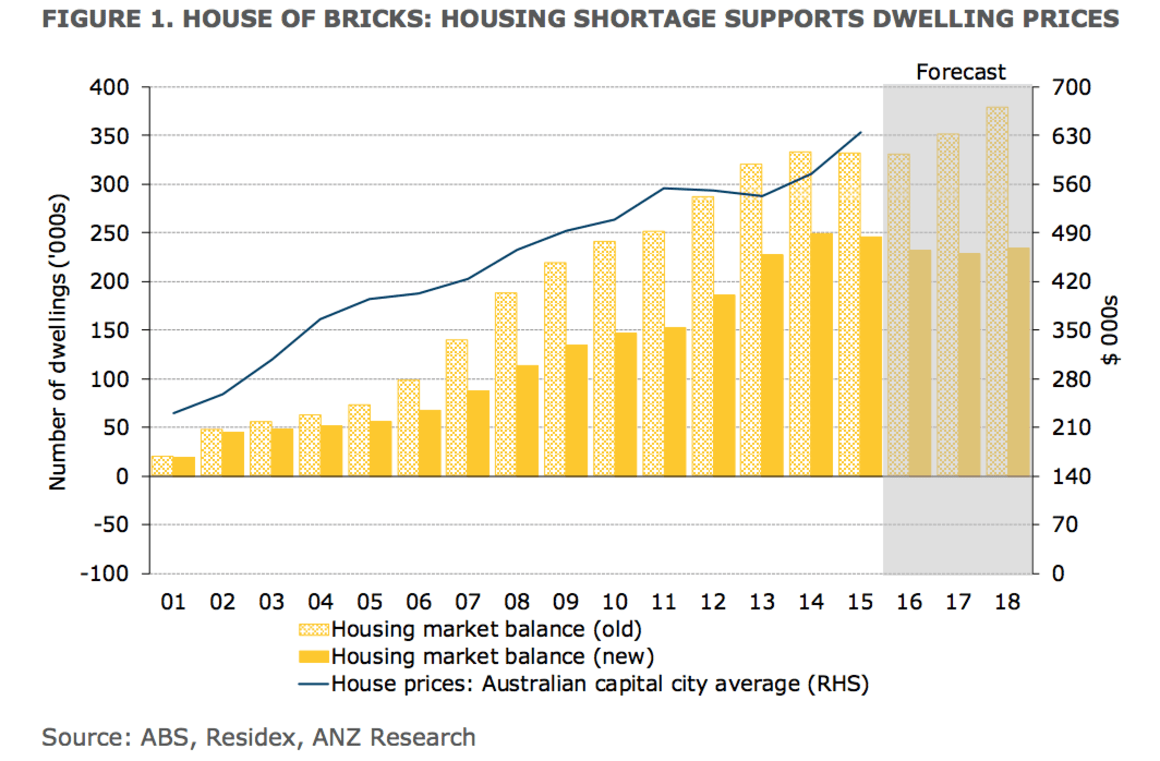

Underlying housing imbalances don’t tend to be important in explaining short-term changes in dwelling prices. A strong increase in the national underlying housing shortage, however, has provided fundamental support to dwelling prices over the past decade, it says.

Foreign investment in Australian housing has increased sharply in recent years, providing a boost to new housing construction. However, the net impact of foreign investment on the supply of housing, and the housing market balance, is difficult to quantify due to limited reliable information about the number of unoccupied foreign investor dwellings.

Housing construction booming; population growth slowing

Australian housing construction is booming but population growth has slowed, prompting speculation by some commentators that Australia’s housing market has, or will soon, have a surplus of housing. The market and media are flooded with views on the state of ‘balance’ in the Australian housing market. These views conclude that housing is either in surplus, balance or shortage depending on whether ‘the market’ refers to: the mortgage/sales market; annual population and housing construction flows; or long-term housing requirements and housing construction, in other words, what we estimate as the underlying housing market balance.

Analysis of demographics and housing construction shows that in the 20 years to 2005 Australia’s annual population growth fluctuated modestly around 218,000 people (1¼% y/y on average). Between 2006 and 2008, however, annual population growth increased sharply, to a peak of 460,000 people (2.2% y/y) in December 2008. This was largely because of very strong net overseas immigration. Over the past ten years, Australia’s population has increased, on average, by around 360,000 people per year (1.65% y/y).

Dwelling construction has struggled to keep up with Australia’s housing requirements (Figure 2). Only recently has housing construction broken away from a long-term cyclical reversion to annual housing completions of approximately 145,000 dwellings. This has reflected a surge in construction of high-rise apartments, particularly in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane.

Consequently, until recently almost a decade of underbuilding has driven a sharp run-up in Australia’s underlying housing shortage. Assuming that the housing market was in long-term cyclical balance – that is, the market wasn’t maintaining a long-term cyclical surplus for a 20-year period to 2005 – housing construction levels have only recently ‘caught up’ to annual housing construction requirements. That is, the surge in higher-density housing construction has driven housing construction levels to match annual underlying housing demand for the first time since 1995.

Based on our expectations of housing construction levels easing moderately from recent all-time highs in the coming years (from 220,000 dwelling starts in 2015 to 205,000 in 2016 and 198,000 in 2017) and slowing population growth (from 1.35% in 2015 to 1.30% in 2016), Australia’s underlying housing market balance should moderate in 2016 and 2017 (Figure 3).

What does the market balance mean for Australian House Prices?

An underlying shortage of housing has little explanatory power for short-term price growth, which is largely a reflection of: housing affordability (ie house prices compared to household income and mortgage rates); housing market sentiment; home buyer preferences; and housing market policy/regulation.

For example, the underlying shortage of housing in NSW continued to increase strongly through the recent periods of falling house prices in 2008-09 and 2011-12. However, an underlying housing market shortage (or existence of pent-up unsatisfied housing demand) does provide significant support to the long-term level of house prices, offsetting the downside risk to prices from short-term/cyclical factors (Figure 1). Looking ahead, markets with significant unsatisfied housing demand, particularly Sydney, have limited downside risks to prices absent unexpected shocks to household incomes.

That said, short-term/cyclical factors that drive house prices lower are likely to have more amplified and longer-term impacts in housing markets with weaker supply-demand balance fundamentals. That is, housing markets currently experiencing strong growth in new housing completions (ie inner-CBD Melbourne apartments, Western Sydney housing) and/or sharply weaker population growth (ie WA and Queensland mining regions) are likely to be more exposed to cyclical price falls than other markets.

In addition, house prices in markets that are considered more-or-less ‘in balance’, such as Adelaide, Hobart and Canberra, have much softer fundamental support and are more exposed to regional economic conditions.

What's changed: Why is the housing market shortage lower?

The Australian housing market has experienced some significant changes in recent years, including an increasing gap between home deposit and mortgage servicing affordability, stronger consumer preferences for higher-density dwellings and a strong appetite for housing as an investment asset.

How do these changes impact on our estimation of the housing market balance? The main assumptions that have been impacted by these changes are household formation rates and demolition rates – both of which have lowered our estimates of underlying demand for housing.

Household formation rates: to reflect subdued first home buyer activity and difficult home deposit affordability we have revised our historical and projected household formation rates lower (ie increasing the notional number of persons per household)

Demolition rates: the issue of urban congestion, or concentrated population growth in the major capital cities, has increased housing demolition rates. This has been reflected by a strong increase in higher-density dwelling (apartment and townhouse) construction in inner-city locations in recent years.

Foreign investors and Australia's housing market balance

Foreign investment in Australian housing has increased sharply in recent years, raising some concerns about the impact of foreign purchases on domestic housing market conditions. Most notably, these concerns have centred on the impact this has had on price growth. A lack of reliable and timely data1 on foreign investor purchases of

Australian housing makes it difficult to draw evidence-based conclusions on the net impact of recent activity on house prices, with most views based on anecdotal information.

However, assuming that the majority of foreign purchases are compliant with existing policy (ie. each purchase adds at least one new dwelling to the housing stock) it is fair to conclude that foreign investment has provided a boost to the supply of new housing and likely had little direct impact on underlying demand (depending on the motivation for the foreign investor purchase).

While the net impact of foreign investment is likely to provide limited direct support to demand for housing through household formation and population growth, it could add to underlying demand through a higher proportion of vacant or unoccupied dwellings. Similarly, there is little reliable data on this impact, with some data indicating a strong prevalence of ‘ghost towers’ and some apartment developers of the view that most foreign investors are tenanting apartment purchases for rental yield as well as capital security.

Consequently, we haven’t built any assumptions about the impact of growth in foreign investment to the proportion of vacant new dwelling completions. However, the 2016 ABS Census will be an important source of current information on the impact of foreign investment on underlying housing demand and Australia’s housing market balance.

Our overall view though is that foreign investment is likely to have eased underlying market balance pressure in the major capital cities.