The economic and financial impact of the Corona Virus: Shane Oliver

EXPERT OBSERVER

The last few weeks have seen escalating concern that a new coronavirus (called 2019 novel coronavirus or nCoV) originating in the Chinese city of Wuhan in Hubei province will become a global pandemic.

Concern has been heightened after the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the outbreak an “international public health emergency” on 30 January and the number of cases has continued to escalate.

While this is first and foremost a human crisis, there has been increasing concern that the associated disruption to economic activity will trigger a global economic slump.

Consequently, share markets have seen falls (ranging from three per cent for global and Australian shares to around seven per cent for Asian shares and 12 per cent for Chinese shares), commodity prices have fallen, and bond yields have collapsed again.

While the current situation is highly uncertain, the experience with SARS, bird flu, swine flu & Ebola highlight worst-case pandemic fears don’t usually eventuate.

What do we know about this Coronavirus

Here is a summary of information regarding nCoV:

Coronaviruses circulate in animals but can be transmitted to humans and affect the respiratory system. SARS in 2003 & MERS in 2012 were examples. Symptoms can be treated but there are no vaccines or antiviral drugs for them (at present). Like SARS, nCoV looks to have originated in wildlife markets in China.

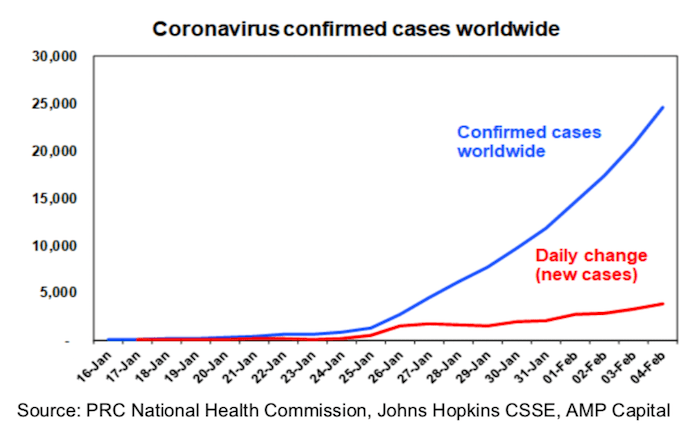

So far there are over 24,500 confirmed cases worldwide, with 99 per cent of cases in China. But the number of cases is still rising rapidly and more/faster testing could mean many more with spikes in the number of new daily cases.

So far the mortality rate is running at two per cent which puts it above swine flu but well below SARS (which settled around nine per cent). And of those dying, its mainly been older people or those with pre-existing conditions (as with common flu).

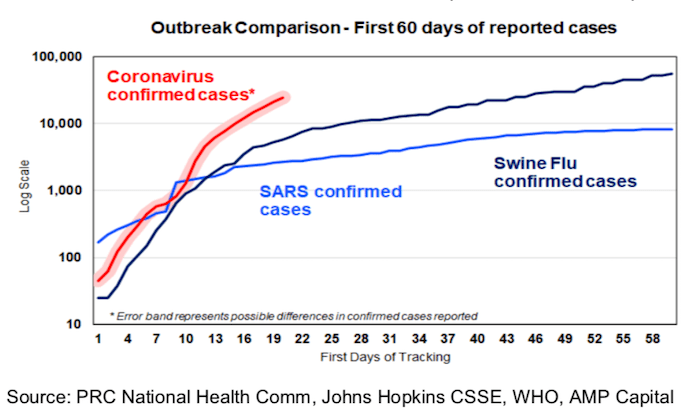

Against this, nCoV has been more contagious with total cases well above those for SARS (8000) and patients can be contagious but without symptoms for one to two weeks.

Containment measures – notably in China – have been more aggressive and started earlier than in the case of SARS. These include restricting travel into and out of Hubei province and various countries have restricted (and in some cases banned) foreign travellers entering from China.

Past experiences

To provide some context it is worth reviewing past pandemics – both real and feared.

There were three influenza pandemics in the last century: 1918-19, 1957 and 1968. The 1957 and 1968 pandemics are estimated to have killed up to 4 million people. However, the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic was the most severe.

While the mortality rate was low, up to 50 million people died worldwide. With a big proportion of the population staying at home, economic activity was severely disrupted, although this was compounded by the ending of World War I.

US industrial production slumped 18 per cent between March 1918 and March 1919. Australian real GDP slumped 5.5 per cent in 1919-20 (but then rebounded 13.6 per cent in 1920-21). The share market impact is hard to discern given the ending of WWI, however US and Australian share markets rose through much of the pandemic period.

The SARS outbreak of 2003 is a more useful guide.

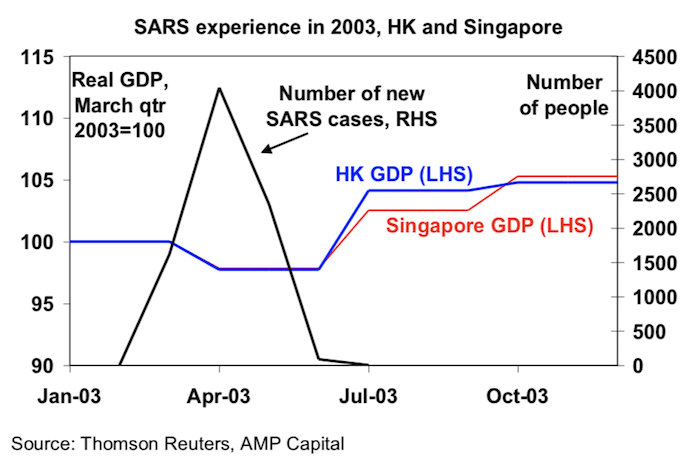

After emerging in China around February 2003, SARS infected about 8000 people (mostly in Asia) in 30 countries over a five-month period and had a mortality rate of about nine per cent. SARS had a big negative impact on the countries most affected as people stayed home for fear of catching it.

GDP in China, Hong Kong and Singapore slumped by over two per cent in the June quarter of 2003. Growth then subsequently rebounded.

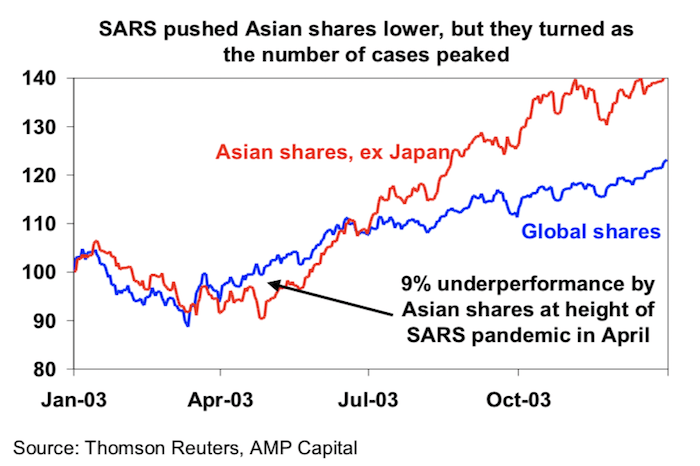

Reflecting SARS, Asian shares fell in April 2003, even though global shares started to move out of a three year bear market from March. The April 2003 low in Asian shares coincided with a peaking in the number of new cases.

Most pandemics have taken 6 to 18 months to run their course and peter out as measures are taken to slow their spread (eg. hygiene, quarantining, banning gatherings, preventing travel). SARS ended quicker due to the nature of the virus and rapid action by authorities.

In 2005/2006, there was significant concern that a severe strain of bird flu (called H5N1), which was resulting in human casualties, mainly in parts of Asia where people had contact with chickens, would mutate into a form that was readily transmissible between humans.

However, this didn’t really eventuate and as such the economic impact was modest although it did cause bouts of volatility in share markets. Similarly, concern that the spread of swine flu would become a global pandemic rattled share markets for a while around April 2009, and Ebola did the same in 2014, but both quickly faded.

The economic and financial impact of nCoV

After strong double-digit gains over the last year and with investor sentiment pushing up to high levels indicating a degree of complacency, share markets were at high risk of a correction in mid Jan and the fears around coronavirus have provided the trigger.

Given their greater sensitivity to Chinese growth, commodity prices like Chinese shares are down by more and the Australian dollar has fallen to October lows below $US0.67. What happens from here depends on how long it takes for the outbreak to be contained. The higher number of cases than with SARS or swine flu suggests a greater economic impact.

But given the range of possibilities, the best way to get a handle on the economic and investment market impact is to consider several scenarios. Here we consider two.

1. Containment within the next month or two – the number of cases continues to rise but it remains mainly contained to China (and Hubei) and the number of new cases starts to peak in the next month or so. This would allow travel restrictions to be removed by the June quarter. Under this scenario:

GDP in China and parts of Asia would likely take a two to three per cent hit (taking Chinese GDP growth from six per cent year on year in the December quarter to three to four per cent yoy in the current quarter) as workers stay home and travel dries up. With the Chinese economy now being four times the share of global GDP it was at the time of SARS, this along with some drag on growth in developed countries would knock world growth to around 2.5 per cent year on year (from around three per cent). However, growth would rebound in the June quarter as travel restrictions are removed and things return to normal.

Australian growth could see a 0.2 per cent hit in the current quarter mainly due to the loss of Chinese tourists (which account for 20 per cent of tourism earnings and 0.2 per cent of GDP) but also lower raw material demand and an impact on confidence. With the bushfire impact this could see GDP contract, but growth would rebound in the June quarter.

Against this background share markets, commodity prices and the $A could still fall a bit further in the near term but would quickly rebound by the June quarter. Easier than otherwise monetary and fiscal policies - with more stimulus measures already announced in China - would aid this.

2. Global pandemic – the number of cases continues to escalate beyond China and aren’t contained until say mid-year.

This scenario would see a bigger and longer negativeimpact on economic activity. Global travel would collapse. Many would simply not come into work – a reasonable estimate is around 20 per cent of workers, although this might be spread over time.

This would see a sharp slump in global GDP and the risk of global recession. Australia would not be immune and would likely see two negative quarters of growth with flow on to education exports to China (which accounts for another 0.6 per cent of Australian GDP).

Share markets would likely fall sharply – maybe by 20 per cent or so - reflecting the huge economic uncertainty. Cash would be the place to be. The $A could fall to around $US0.60.However, economic activity would rebound quickly once it’s clear the pandemic is under control. Share markets are likely to anticipate this. But this wouldn’t occur till the second half of the year.

Concluding comment and what to watch

While there is reason for concern and it is easy to dream up nightmare scenarios, the experience with SARS, bird flu (with “predictions” it could kill as many as 150 million people) and the mini panic regarding swine flu and Ebola tell us that the worst case fears of pandemics usually don’t come to pass. Rapid containment measures provide some confidence this will be the case. As such, our base case scenario (with 75 per cent probability) is one of containment over the next month or two. This could still see more downside in share markets and bond yields in the near term, but they are likely to rebound by the June quarter as economic growth rebounds. The key things to watch are:The daily number of new cases – the SARS experience saw markets rebound once this showed signs of peaking.

The spread of new cases and deaths in developed countries – if this remains limited then markets will also get more confident that the economic fallout will be short lived.

DR SHANE OLIVER is the Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist AMP Capital.