House prices will fall in a “slow bleed” fashion: Steve Keen

Steve Keen says he never expected house prices to fall in a huge leap – a point for which he has been figuratively flayed alive by the mainstream media – but does expect house prices to fall like a “slow bleed”.

In 2008, Keen said house prices would fall 40% once the financial crisis had "washed through the system".

In November 2009, he walked up Mount Kosciuszko wearing a T-shirt that said: "I was hopelessly wrong on house prices!" after losing a bet with Macquarie's Rory Robertson.

But he now contends the GFC has never ended and will continue - on and off - over the next two decades.

The volatility in the housing market certainly remains.

Dwelling values fell by a surprising 1.7% in the past two months despite a rate cut in May, according to RP Data-Rismark, while the ABS had capital city house prices up just 0.1% over the March quarter.

Of further concern, the most recent Real Estate Institute of Australia (REIA) Housing Affordability Report has recorded plummeting mortgage approvals in the key first-home buyer market, particularly in NSW and Queensland.

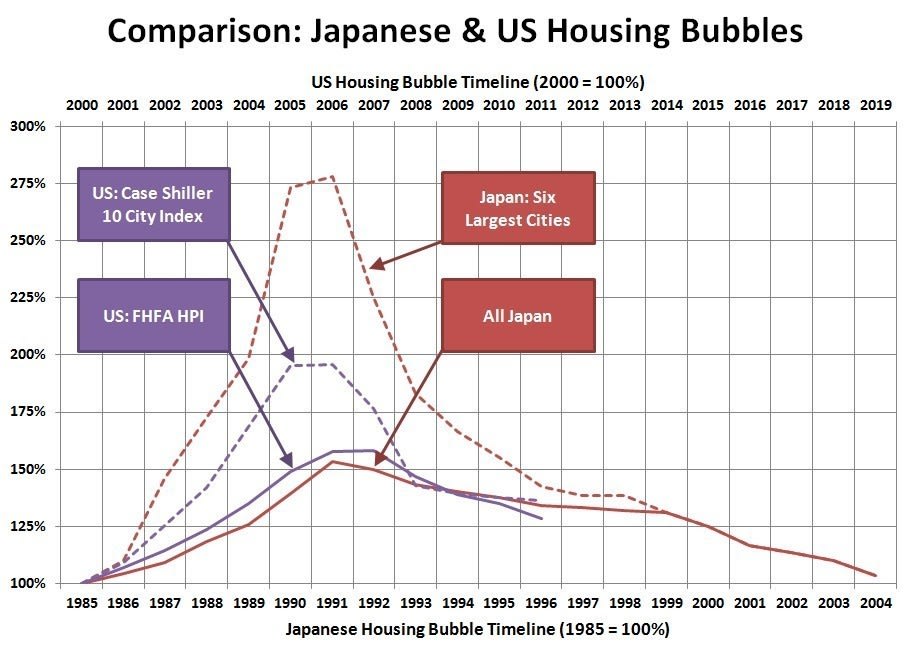

Keen had anticipated in 2008 when the GFC was in full swing a faster Australian price correction than what has happened in Japan, where house prices in Japan’s six largest cities rose around 175% from 1985 to 1992 and then fell back to their starting point between 1992 and 2000 – but slower than the dramatic GFC plunge in the US.

Source: Seattlebubble.com

Instead Australia underwent a modest house price correction as the latest RBA chart pack show, with five out of the six biggest capital cities now having property markets trending upwards, though at uneven rates of growth - but nothing like the corrections in the US and Japan.

“I got the magnitude wrong. But I?never had this idea of a huge drop?tomorrow,” Keen says in an interview with BRW magazine.

He has called the most recent modest rally in house prices (up 2.9% over the past 12 months according to RP Data) a “suckers rally” with price gains spurred on by government incentives, low interest rates and the resources boom.

Keen does admit that he got other forecasts wrong, including expectations that there would be a massive de-leveraging among households, something which has only occurred on a modest scale.

The most recent RBA chart pack graphs show household debt to income soared from the early 1990s to peak at around 150% to income in the mid-2000s.

It started to dip as the GFC hit around 2007, but government incentives like the doubling and tripling of first-home owner grant (under the boost scheme) encouraged people to borrow again.

Household debt now sits just under 150% - hardly the massive correction Keen anticipated and a mistake he is happy to acknowledge.

Keen says mortgage debt is rising because variable mortgage rates remain the preferred home loan product in Australia while fixed-rates dominate in the America.

This means that borrowers get an instant mortgage repayment benefit when the cash rate is cut.