Four reasons negative gearing won't be squashed: Pete Wargent

Most of the debate surrounding so-termed "negative gearing" in Australia circles endlessly debating one point: were the rules regarding deductions to be quarantined again as they were previously in 1985, would rents increase at eye-watering growth rates?

In other words, are the existing rules an effective rental subsidy that are now pushing rental growth down below the rate of inflation.

It's something of a hypothetical debate.

Firstly that's because looking historically nobody knows the counter-factual (i.e. would rents have kept rising beyond 1987 had the rulings not been reversed?). And secondly, because to all intents and purposes there were no property investors in the lead up to 1985, so conditions today are completely different.

In the year 1985 investor finance accounted for a miserly 13% of total housing finance, compared to a whopping 40% or a stonking $139 billion of domestic investor finance over the past 12 months alone.

I'm sure that nobody believes for a minute changes to the tax law would force rents higher in Kununurrra or Kurrajong, but research has consistently shown that there is a heavy concentration of investor-owned dwellings in the inner- and middle-ring suburbs of our largest capital cities - remove a portion of the rental stock in these locations and some increases in rents would be certain.

Moreover, changes to the tax law would quickly undo the system which has succeeded in kick-starting the greatest residential building boom in Australia's history, which will soon result in an oversupply of dwellings in at least six of our capital cities, and possibly eight of them.

With a nascent boom in residential construction now underway and home starts breaking record highs, the tax law won't be changed because it's creating the supply that's needed, estimated at more than 180,000 dwellings per annum.

Budget impacts

The rents argument is a sideshow in any case. It's often also argued that negative gearing rules should be scrapped in order to "save" $4 billion from the budget and $2 billion per annum going forward but this is a flawed notion.

Between 1985 and 1987 the numbers on the New South Wales housing waiting list reportedly increased alarmingly by almost a third from fewer than 110,000 up to nearly 140,000 in only 18 months, a trend which was immediately reversed upon the re-introduction of the previous ruling on interest deductions.

In Britain, approximately 17% of households live in social housing. The problem in Australia is that at a measly 4.5% of total housing stock, public housing "cannot provide a realistic alternative to a private rental market for existing homeowners" - AHURI's 2010 report on the future of public housing explains in detail the many reasons why:

"Through the stimulus package, the Commonwealth put $6 billion on the table to build 20,000 houses. That’s lovely. But the shortfall in social housing is 160,000 dwellings. So either they find another, whatever that is, another $50 billion - no way!".

Other estimates put the shortfall at up to 200,000 dwellings, and without adequate additions the social housing shortfall can only get worse.

Source: AHURI

As highlighted in AHURI's report, with Commonwealth and state elections held in 3-year cycles, committing large amounts of money for long-term capital housing investment is seen to be risky for politicians. It's just not going to happen.

And indeed, there is no intention of addressing underfunding of the sector, with core funding declining in real terms by 26% between 1996 and 2008. Confirmed the AHURI report "there is no way that Commonwealth or state governments are going to kick-in capital funding which is going to enable social and affordable housing to grow at 2% per annum".

Australia is projected to have 4.3 million more households in the 25 years to 2036, and (andmillions more by 2055, particularly if my assumptions on population growth are proved correct) so the total demand for rental accommodation will be beyond huge.

Source: AHURI

As I will discuss below, the solutions can only come from private individual and offshore investors, with upwards pressure on prices encouraging more construction, which is exactly what is playing out right now.

Case study: Public housing in Victoria

Having been the subject of an audit in 2012, public housing in Victoria is worthwhile case study.

In my living purgatory as an auditor I wrote seemingly endless reviews and reports for Central Banks, Treasuries, Ministries of Finance, Government Finance Departments and the like - the reality is that such reports in draft form often promise to be somewhat spicy, but after internal reviews and by the time final reports are issued the recommendations tend to be watered down and uncontroversial.

I don't think I've seen many more damning auditor reports than the one issued by the Auditor-General to the Legislative Assembly on the subject of "Access to Public Housing".

The main source of social housing in Victoria is public housing, yet as at the audit date there were fewer than 83,000 social housing dwellings in Victoria, 65,352 of which were public housing, owned and managed by the Department of Human Services (DHS).

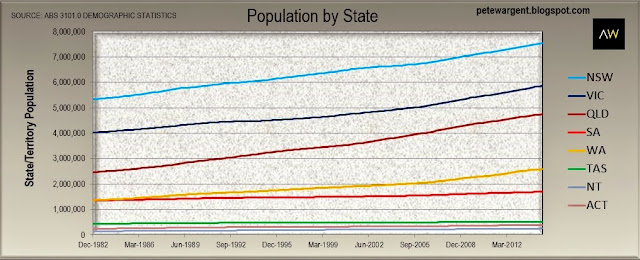

Victoria's population, meanwhile is rapidly approaching 6 million and counting.

The chart below shows those 65,253 public housing dwellings by type and location at 30 June 2011.

Source: Auditor General

A $17.8 billion property portfolio, housing around 127,000 Victorians, noted the auditor, requires “informed, cohesive and comprehensive asset management”, but condemningly the audit found no such systems in place.

Here are four reasons that public housing is not a viable alternative to the provision of rental stock by private investors.

This article continues on the next page. Please click below.

Reason one - The public housing financial model is unsustainable

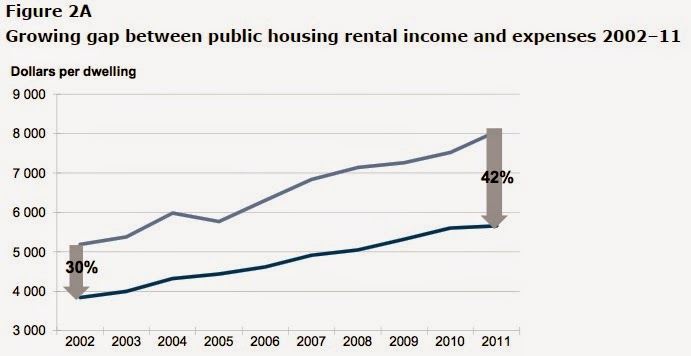

The situation for public housing was found by the auditor to be “critical” and public housing’s operating model “unsustainable”.

Funding for the division in 2011–12 was $402 million, with set aside $169 million for social housing activity, and the audit found that the operating model for public housing, with costs comfortably increasingly exceeding revenues, to be unsustainable.

The review found that in 2011 operating costs exceeded rental revenue by a thumping 42%, up from 30% in 2002. The review further forecast that the division's deficit would more than double from $56 million in 2011 to $115 million by 2015 and that all cash reserves would be exhausted by within two years.

Source: Auditor General

The division’s short-term strategies to address its financial position had only deferred and compounded the problem using short-termist band aid solutions to address its dire financial situation.

Such short-term solutions included the reduction of stock acquisitions, the deferring of preventative maintenance, and funding deficits by utilising cash meant for long-term programs - which only compounded the issue, particularly the growing maintenance liability.

While rent and other property income had increased by 7% (in nominal terms by $24 million between 2007 and 2012), operating costs had spiralled by 27% or $92 million in nominal terms over the same period.

Reason two - Public housing stock is grossly inadequate and under-supplied

The Auditor-General found that demand for public housing had easily exceeded supply over the preceding ten years - the cost of living and household numbers had increased and the availability of affordable housing had decreased.

The demand for public housing is measured as the number of households that have applied for public housing and are on the public housing waiting list.

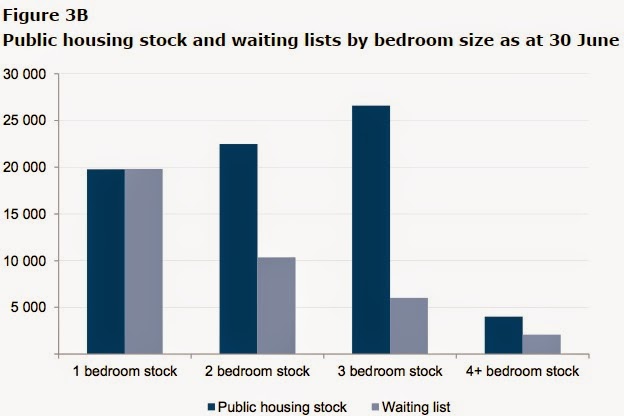

The audit found that as at 30 June 2011 there were more than 38,000 households on the waiting list – and once applicants are approved for public housing, they still have to wait to be housed.

In 2009–10, applicants who had received a priority allocation waited an average of 8.5 months for housing, and non-priority applicants wait several years.

Reason three - Public housing stock is grossly mismatched

The tenant profile of public housing has changed substantially over time.

Large estates built in the 1960s were intended for working families on low to moderate incomes as a transitional measure before moving into private housing. Most properties were accordingly built to meet the needs of families as opposed to an increasingly single and older tenant group.

Today, however, public housing now serves an increasing proportion of elderly, single and economically and socially disadvantaged tenants.

Thus the need for one-bedroom dwellings has increased dramatically while the need for larger dwellings has decreased. The chart below shows the mismatch between public housing stock, and demand as reflected by the public housing waiting list.

Source: Auditor General

Unfortunately, legislative, regulatory and policy settings prevent authorities from actively trading public stock to help finance necessary dwelling upgrades (or from expanding stock levels by changing the mix of densities, dwelling types and locations to match the needs of target households).

As was shown in the above graphic, at the audit date it would have required almost 100% turnover of households in one-bedroom properties to meet waiting list demand, as compared to only 25% for three-bedroom properties.

The National Housing Supply Council projected that the demand across Australia from older householders for single households would increase from 86,500 to 189,800 between 2010 and 2029.

Reason four - The quality of public housing stock is in sharp deterioration

The public housing portfolio was found to be in a seriously deteriorating condition with the division estimating that 10,000 properties (or 14% of the total) would reach obsolescence over the following four years, and a significant mismatch of properties to tenant needs.

The asset base was found to be deteriorating awfully with 42% of housing stock being over 30 years old. Of course, properties of this age generally require more frequent and larger scale repairs, maintenance and upgrades.

Yet the division was found not to have articulated any long-term objectives or plans at all for public housing.

A property portfolio approaching $20 billion in value housing 127,357 Victorians, requires an "informed, cohesive and comprehensive asset management system", but in fact no such systems were found to be in evidence.

In 2011 well over 14,000 dwellings (25%) had not been assessed for over three years, with 2,400 of those not inspected for over five years, in spite of the supposed divisional policy to assess all properties at least three-yearly.

The division also estimated that, due to limitations within the system, maintenance costs of $298 million across the portfolio were, on average, understated by a whopping 138% for each property.

The wrap

As concluded by AHURI, is very little optimism that public housing can or will play a significant role in the overall housing system, or contribute in any significant way to addressing the supply of affordable rental housing stock.

Perhaps more importantly, there is no political will at all to invest in public housing.

Private housing is all there is, and government policy has clearly concluded that the road ahead will necessarily involve incentives for Mum and Dad investors to provide rental accommodation.

Institutional funds and the private sector won't touch the sector because rental returns are too low.

Indeed the Treasury was approached with a request for investment from the Future Fund and the response was exactly that - the Future Fund will not invest in residential property because rental returns are too low.

So if the private sector won't invest in rental housing because the returns are too low, and the Australian government won't invest its money there either, the only remaining alternative is to incentivise individual investors to do so.

And that's why the negative gearing rules won't be squashed.

PETE WARGENT is the co-founder of AllenWargent property buyers (London, Sydney) and a best-selling author and blogger.

His book 'Four Green Houses and a Red Hotel' is out now.