"Our distrust is very expensive": We can't have a trustworthy financial market without an honest property system

In June 2013, as the Senate voted unanimously to hold an inquiry into the corporate watchdog ASIC. Chairman, Greg Medcraft, gave a keynote speech to the ‘Global Investor Education Conference’.

Using the allegory of a stool, Medcraft identified three essential components needed for an “efficient and effective” financial market;

- A robust regulatory framework that is enforced effectively

- A competitive financial services industry that offers quality products and services, and finally

- Investors who feel confident when participating in the market, and are able to make sensible and informed financial decisions.

Concluding; “If one of the legs is missing, the stool will fall over”.

However, recent findings from theSsenate inquiry, along with media reports exposing wide spread corruption, political lobbying, and financial fraud within the banking industry, have proved all three legs of Medcraft’s stool are missing.

The regulator is at best, a totally ineffective operator, at worst, allegedly guilty under the Crimes Act for actively concealing information from victims of financial fraud.

Charged with overseeing a sector that is more than 80% owned or tied to the big four banks and AMP , the government will now cut funding to ASIC by $120.1 million over the next five years, while also watering down recommended reforms from the Future of Financial Advice report.

The retrograde changes will allow planners to claim they’re working in the best interests of clients, whilst still collecting ‘targeted’ rewards for pimping their employer’s products – moves that will do little to inspire confidence in the public, or improve the quality of products offered.

When asked about the budget cuts, Medcraft commented: "What it means is that we do not have the luxury of doing as much proactive surveillance."

But, ASIC have not been doing ‘proactive surveillance’.

They have been systematically turning away and ignoring consumer concerns, resulting in more than 1,100 people losing millions, due to alleged questionable practices by advisers from the CBA and other financial institutions.

It’s hard to conceive how Medcraft concludes we have a ‘competitive financial services industry’.

Together, Australia’s Big Four control more than 80% of domestic assets - that is, assets held by any individual, business or organisation resident in the country.

They enjoy 89% of total banking sector profits, 82.5% of the net interest income from ADIs, loans, and advances, and 83.2% of total interest income from residential mortgages.

Moreover, bankers have important privileges. They hold the keys to the economy. Want a house? You’ll need a mortgage. Want an education? You’ll need a student loan.

They have the power to endogenously create (from thin air) and direct the flow of their own, and other people's money - amplifying the inflationary and deflationary swings of asset cycles – all backed by taxpayer-funded insurance should their plans go awry.

Meanwhile, investors battling an economy tilted toward privilege that does not allow workers on an average wage to achieve a comfortable retirement through saving alone, are charged with assessing the risks associated with an increasing array of elaborate financial products. This keeps dependence on industry ‘advice’ from sales agents whose moral judgement is subverted by the fees, commissions, and kickbacks they receive.

The system is pinned on trust and as American lecturer, Ralph Waldo Emerson once commented: “Our distrust is very expensive."

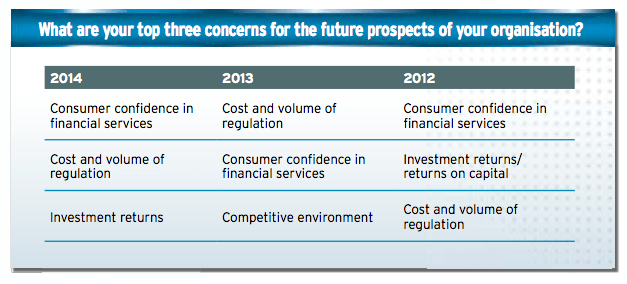

When trust breaks down, so do economies. It is therefore no surprise that in the latest annual survey of chief executives, put together by the Financial Services Council – ‘trust’ comes top of the list, followed by regulatory overload and sustainability, as the top three threats to industry profits,

“Industry leaders recognise there is a need to restore consumer confidence following global events such as the financial crisis.”

The wording in the report is mild, placing both focus and blame on the ‘GFC’.

However, former ASIC employee, lawyer and whistleblower to the recent senate inquiry, James Wheeldon, paints a picture of what is little more than a sales industry, spruiking its goods with glossy prospectuses, celebrity glamour shots, arrows pointing ever skyward, while the serious warnings are wrapped up in incomprehensible language and buried deep within the reports.

He cites the example of financial service provider RAMS, which in 2007 offered shares in its Home Loan Group - gifting founder and major shareholder, John Kinghorn, $500 million - before collapsing just three weeks later as a result of a ‘major liquidity disruption’.

At the time RAMS claimed it was, ‘the victim of unforeseeable circumstances’.

In reality, the ‘major liquidity disruption’ hinted at within the small print of the report, was already underway.

Investors who purchased RAM’s Home Loan shares at the time, did not see the economic collapse coming - much less so those who bought into real estate investment trusts (REITs) during the run up to the peak.

This is because the advisors in the banking industry will never acknowledge how Australia’s rising land values, far from being indication of economic prosperity, bear their consequence in a gradual destabilisation of the economy.

Article continues on the next page. Please click below.

More than half the value of household assets (54%,) is comprised of real estate. While superannuation along with life policies - a significant and rising percentage of which is also invested into property - accounts for a further 25%.

Additionally, property also makes up a large percentage of stock market value, not just in the form of REITs and housing related companies, industry studies indicate that real estate makes up more than 25% of the assets on an average corporate balance sheet.

But, while it is well accepted that a housing bubble yields disastrous consequences and should be avoided at any cost, (although, is in fact promoted at great cost). There is far less focus on how fluctuations in market prices bear a consequential affect on business activity, which ultimately yields to the same result.

Statistician Victor Niederhoffer and Laurel Kenner, cover the subject briefly in their book, Practical Speculation, with additional updated research that can be sourced on their website Daily Speculation.

They make the point that stock market investors can gain valuable insights from studying the land cycle - dispelling the conventional belief that gains in stocks drive up real estate prices because people have more money to invest.

Using a REIT index as a general proxy for values, they note an “amazingly” large correlation between changes in property prices over the course of one quarter, and the S&P 500 index, the next.

Their research demonstrates that quarterly declines in REIT prices, can forecast overall market gains at close to twice the normal rate in the following quarter - yet, when viewed in reverse: “the correlation between the change in stocks in one quarter and the change in REIT prices the next quarter however, was close to zero.”

The research helped them conclude that it is the housing cycle that ultimately leads the business cycle – not the other way around, as is often assumed.

The authors employed their analysis to successfully predict an imminent decline in real estate values in March 2002 – receiving wide spread criticism from industry advocates who suggested their warnings belonged “in the trash can”.

However, as they go on to note:

“The torrent of vituperation is instructive in many ways. As economists who study the subject invariably conclude, contradictions are likely just when developers and banks are most convinced that business conditions warrant expansion.”

The concept, ignored by most real estate advocates is simple enough to understand.

Land is the beginning of all production.

All economic activity needs land – and therefore the value of land has a powerful impact on the activities that take place above.

Lower land prices enable production to expand, assisting small businesses and innovative startups.

On the other hand, an excess of rent - the capitalised tradable value that is locked into the price - leads to a decline in business activity, as owners and tenants are required to take on a higher level of debt, to service the associated costs.

For the lender, it’s an extremely profitable exercise.

Banks quite literally mortgage the earth.

For each new buyer that moves onto a previously paid off plot, a new contract is issued.

Buyers purchase for tomorrow’s capital gains – with rents and company profits used to service the debt rather than expand their core business and the land used as collateral.

Article continues on the next page. Please click below.

“Once upon a time, tenants paid rent for the use of land to landlords. Today, the bulk of those rents are disguised as interest and paid to the financial sector to fund mortgages,” said British economist Fred Harrision.

The process is self-feeding - property prices are valued against recent sales. The higher property prices become, the more buyers need to borrow – the more buyers borrow, the more bank created credit is lent into existence against what is now little more than a speculative premium, encouraging vendors to hold out for ever increasing returns.

The rising appraised market value of a banks' mortgage portfolio coupled with the need to meet shareholder expectations of return, further encourages lending - amplifying the volatility of the cycle, particularly during periods of easy monetary policy.

As the air is sucked out of the productive sectors of the economy, depressing both wages and job growth, increasing the costs of welfare and compromising the ability of monetary policy to stimulate demand. Assets inflate, while the ‘real economy’ stagnates and the sharp rise in interest rates, that typically comes towards the end of the cycle - when it is noted far too late in the game, that prices have exceeded any thread of rationality - is enough to tip the balance.

In the case of a crash, the last buyer in will be the biggest loser. The banks however, will be 'saved'. With land prices now low enough to attract new investment, the stock market, which prices in recovery ahead of time, will be first to advantage.

For the elite, this system works perfectly.

It makes those at the top of the pyramid very rich.

Therefore the economic disasters that derive from this process are passed off as unforeseeable 'Black Swan' events. Except they are not ; they can be predicted with quite a degree of accuracy.

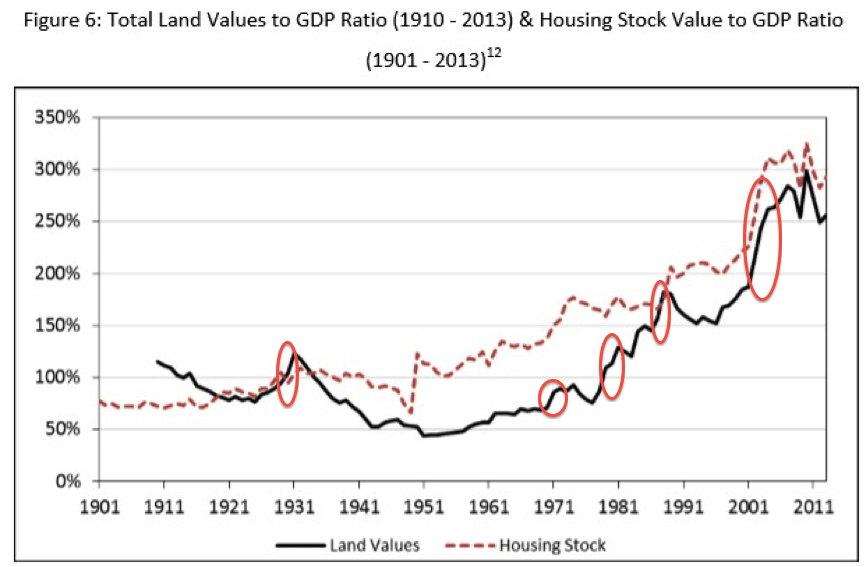

We have enough reliable public data to trace the land-driven boom bust cycles over hundreds of years.

Some of the older data sets include Homer Hoyt's classic 100 Years of Land Values in Chicago, 1833-1933, which details five major crashes that affected not just Chicago, but the whole of the USA.

Real estate analyst Roy Wenzlick, author of the 1936 publication The Coming Boom in Real Estate, produced similar research, monitoring transaction volumes, rents, values and construction into the early 1900s.

Maastricht Professor, Piet Eichholtz's index of prices for the Herengracht canal area in Amsterdam, which begins during the 1600s, an era associated with a fall in land values of 50% – and shows a similar pattern of volatility right through to the late 1900s.

A comprehensive history of cyclical research around the globe, can be found in the work of scholars such as Philip J. Anderson, Mason Gaffney, Fred Harrison, and most recently, the publication Bubble Economics, by Paul D. Egan and Philip Soos, which records the Australian history of speculative land crashes from the 1800s onwards.

The precursor is always a rapid run up in land price to GDP and consequently bears evidence of a marked increase in consumer debt for the purpose of lending against speculation, rather than investment into productive activities.

This has been the trigger for all of Australia’s recessions. The 1890’s, 1930’s and more recently 1974–1975, 1982–1983, and 1990–1991, and would have additionally been the trigger in 2008, had Kevin Rudd not thrown every last penny of a budget surplus (and then some), into propping up house prices and preventing any significant private debt de-leveraging.

Source: Philip Soos

Of course, the clear and obvious link between land price volatility and the ongoing negative effects on both society and the economy, should be enough to push ministers to more than just tinker at the edges of both real estate, monetary and regulatory policy.

As former CEO of the Commonwealth Bank and head of the Financial System Inquiry, David Murray, correctly noted last week, “distorted asset prices” will eventually “cause a correction” resulting in “political pressure on financial systems”.

Political pressure will ultimately fall upon the tax payer to chip in when the institutions that have monopolised the public rents need to be bailed out.

Article continues on the next page. Please click below.

The RBA is also not ignorant of these matters – they were covered in detail in their 24th annual conference in 2012, co-hosted with the Bank for International Settlements:

“The crisis has challenged the benign neglect approach to real estate (and other asset price) bubbles. That approach was backed by a theoretical framework that saw the structure and behaviour of financial intermediaries largely as macroeconomic-neutral and by the belief that policy was well equipped to deal with the consequences of a bust.”

In it, Glenn Stevens noted that;

“Monetary policy cannot surely ignore any incentive it creates for risk-taking behaviour and leverage. Simply expecting to clean up after the credit boom is not sufficient … the mess might be so large that monetary policy ends up not being able to do the job”

Yet monetary policy does ignore it – as do the regulators.

Following the senate inquiry, in July 2014, Greg Medcraft was interviewed by the Centre for International Finance and Regulation as part of a symposium on market and regulatory performance’.

The theme that emerged from the interview and the conference as a whole was the need for a change of culture within the banking sector.

However when Medcraft was asked if he agreed with Governor of the Bank Of England, Mark Carney, who suggested regulation should play a critical role in changing culture, the response was telling;

“No I don’t think the regulator can change culture… it’s not about complying strictly with the law, but just making sure you pass the perception test… how would it look if this became public.”

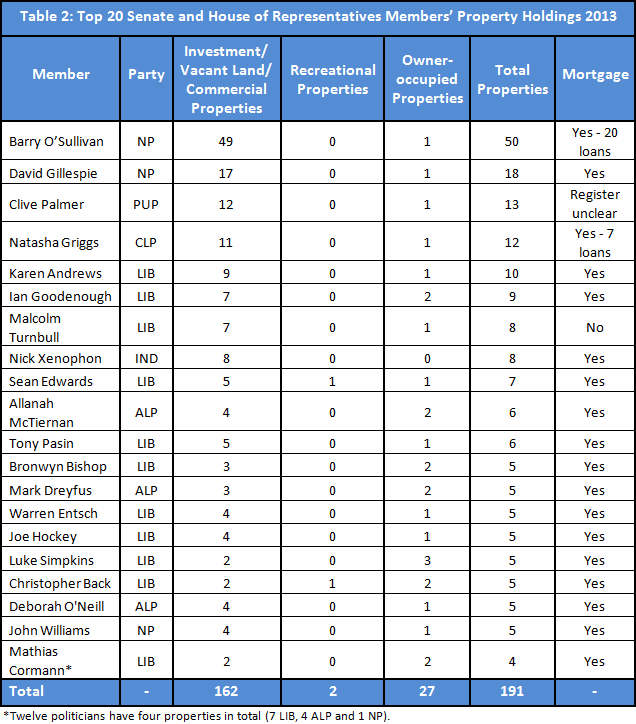

‘How it would look if this became public’ - was discovered, when Lindsay David, Paul D. Egan, and Philip Soos, published details of the dwelling investments held by our Federal members of parliament - causing outrage on social media toward what is a clear conflict of interest impeding the ability of MPs to successfully address issues relating to housing affordability and ultimately head off another financial crisis.

Yet, despite the social and ethical problems that result from the process, our politicians that own substantial investments in real estate are merely the ‘pin up’ boys and girls for an industry, born of a culture that promotes an unsustainable system of leveraged debt and rising land values as the road to both freedom and riches.

It has driven up the cost of housing – damaging the potential of future generations, with a lifetime worth of debt sold as “forced savings”, whilst the interest is re-packaged an into an array of obscure financial instruments, allowing the country’s wealth to gravitate into an elite nuclei of financially strong hands.

Only by removing the accelerants that produces this behaviour – contained in our tax, supply and monetary policies - can we start to address the systemic boom and bust cycles that lay us open to financial crises.

Every citizen in Australia would be richer by a significant margin if we collected the economic rents from, land, resources, banking profits, government grated licences and so forth - the ‘commonwealth’ of the country. And used these to fund society’s needs, rather than inflicting harsh penalties and impeding economic growth, with dead weight taxes on earnings and productivity, to feed an elevated level of speculative demand.

In addition to this, we must remove all barriers that increase the cost of land at the margin, with an overhaul of supply side policy – ensuring cheap land is available for need, not greed.

It’s impossible to have a trustworthy banking system, until we first create an honest system surrounding the fundamental principles of property rights.

Ultimately, this must come by way of a collective and democratic agreement – a discussion over what belongs to you, me, and critically – us.

However, until such time, we remain subject to the self-satisfied complacency of our politicians, who continue to undermine the people’s trust.