Our $300 million propertied federal pollies: How should they influence housing policy?

GUEST OBSERVATION

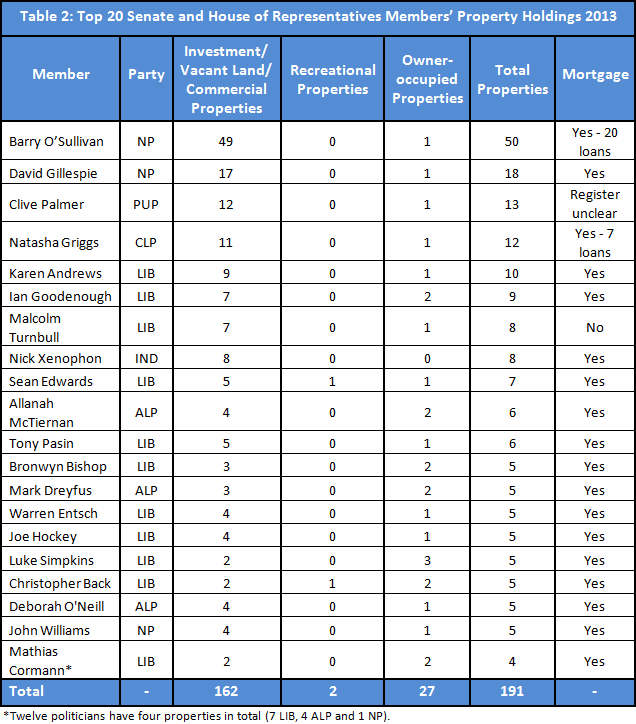

Australian politicians are keen property owners. Data compiled by Lindsay David, Deakin University’s Philip Soos and Paul Egan from the parliamentary register of members’ interests shows the 226 members of federal parliament (both houses) have an ownership stake in some 563 properties. While these properties may be jointly owned with a spouse, this is an average of 2.5 properties per member.

In 2013, the 76 members of the Senate had 202 property holdings and the 150 members of the House of Representatives had 361 property holdings.

Top of the leader board is National Party Senator Barry O’Sullivan with a portfolio of 50 properties. David Gillespie follows with 18 and Palmer United Party Senator Clive Palmer has a seemingly conservative 13, although the total value of Palmer’s properties is unknown (see table below).

Compiled by Lindsay David, Philip Soos and Paul Egan.

The estimated total value of these properties is said to be around A$298 million. This was calculated by multiplying the 563 properties by the median dwelling price of $530,000, as of July 2014. If these properties are located in major cities or other high-value areas the property holding could be substantially higher.

Property, democracy and fairness

Major Australian cities have been feeling the housing affordability squeeze for some time now. Owning multiple investment properties does nothing to ease the upward pressure on real estate prices or to increase first home buyer opportunities. Ensuring housing equality – for example, by providing adequate housing for all social groups – is becoming an increasingly complex task in Australian cities.

When the philosopher John Rawls coined the phrase the “property-owning democracy” he was interested in how property might be used to satisfy the principles of justice as fairness. Rawls could hardly have known the illuminating irony he might cast on the property holdings of politicians.

Should we be alert, perhaps even alarmed, at the real estate investment practices of the guardians of Australian democracy? Well, maybe. Some 94% of the members of federal parliament owned real estate in 2013. More than 50% own investment or commercial property. By comparison, ABS data show less than 20% of the general population owned a property other than the one they lived in in 2012. But it’s politicians that set the taxation and housing policies that attempt to address our housing concerns.

Policy push

Senator Xenophon is currently seeking changes to the Superannuation Act that would allow funds to be released to purchase a first home. This would not put downward pressure on first home buyer housing stock. In fact, it could diversify the investment pool and lead to upward pressure.

According to the register, Independent Senator for South Australia Nick Xenophon has a portfolio of eight investment properties.

A spokesperson for Senator Xenophon said the register was outdated, but confirmed the Senator owns four investment units and his super fund also owns a property (under management). The correct figure is expected to be reflected in the next register of Senator’s interests.

Addressing housing disparity

Australia’s democratic process is predicated on notions of impartiality and transparency. The parliamentary register of members’ interests is an important citizenry “watch dog” mechanism. It is a mechanism that should be employed to monitor the property holdings of Australian politicians and then deployed to call their actions to account.

It is important to note that the research doesn’t show a causal link between property holdings and decisions of politicians. But it would be imprudent to assume prima facie that the property holdings of Australian politicians do not play a role in their political thinking, especially as this thinking relates to housing, taxation or even superannuation policy.

What is needed is a broader discussion about housing disparity that fully acknowledges and accounts for these vested interests and tools of political influence. This should include the politics and interests of the politicians themselves.

The naïve assumption that housing wealth will trickle down through a property-owning democracy have been shattered by the realities of 21st century Australian cities. The question which remains is whether our democratic processes can be reorganised to address these now clearly evident housing disparities. A discussion about the real estate ideologies that underwrite the investment agendas of Australian politicians seems like a fitting starting point.

Dallas Rogers is research fellow at the Urban Research Centre, University of Western Sydney.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.