Housing hoarders: Where the rich pay less and the poor pay more

I was contacted twice last week to comment on news stories that featured young Australians building their way to retirement, through debt, leverage and speculation, on the back of rising property prices.

Described as ‘an entrepreneur,’ another a ‘wonder kid,’ both stories told a similar tale.

A gift from mum and dad had helped with the deposit - living in the family home had enabled investment into areas that may not have suited their 'home' buying requirements.

Rising property prices had enabled equity to leverage into the second acquisition – it was not reinventing the wheel, rather a repeat of an all too familiar theme.

One had managed to reach his sixth investment by the age of 26 (having started at only 19) - both were on their way to becoming property investment advisors – wanting to help others achieve real estate riches too.

“Young buyers are entering the property market as investors” prompted one reporter – which is no more obvious than saying “circles are round”.

Everyone who enters the property market is an investor, I responded.

There would be few in the industry working on the buying side of the equation who had not been involved in what I often term ‘the capital gain game’ – where every option suggested is followed by the question “but which will get the best growth?”

Australia has a lopsided neoliberal economy founded on the back of a 5.1 trillion dollar housing market, over 4.1 trillion dollars of which is irreplaceable land.

We’re slaves to a system where the retirement wealth egg is the family home – our personal economic leverage for all lifestyle and business needs - something that is only achievable if policies are manufactured to ensure values remain high (and climbing), whilst debt levels remain ever affordable.

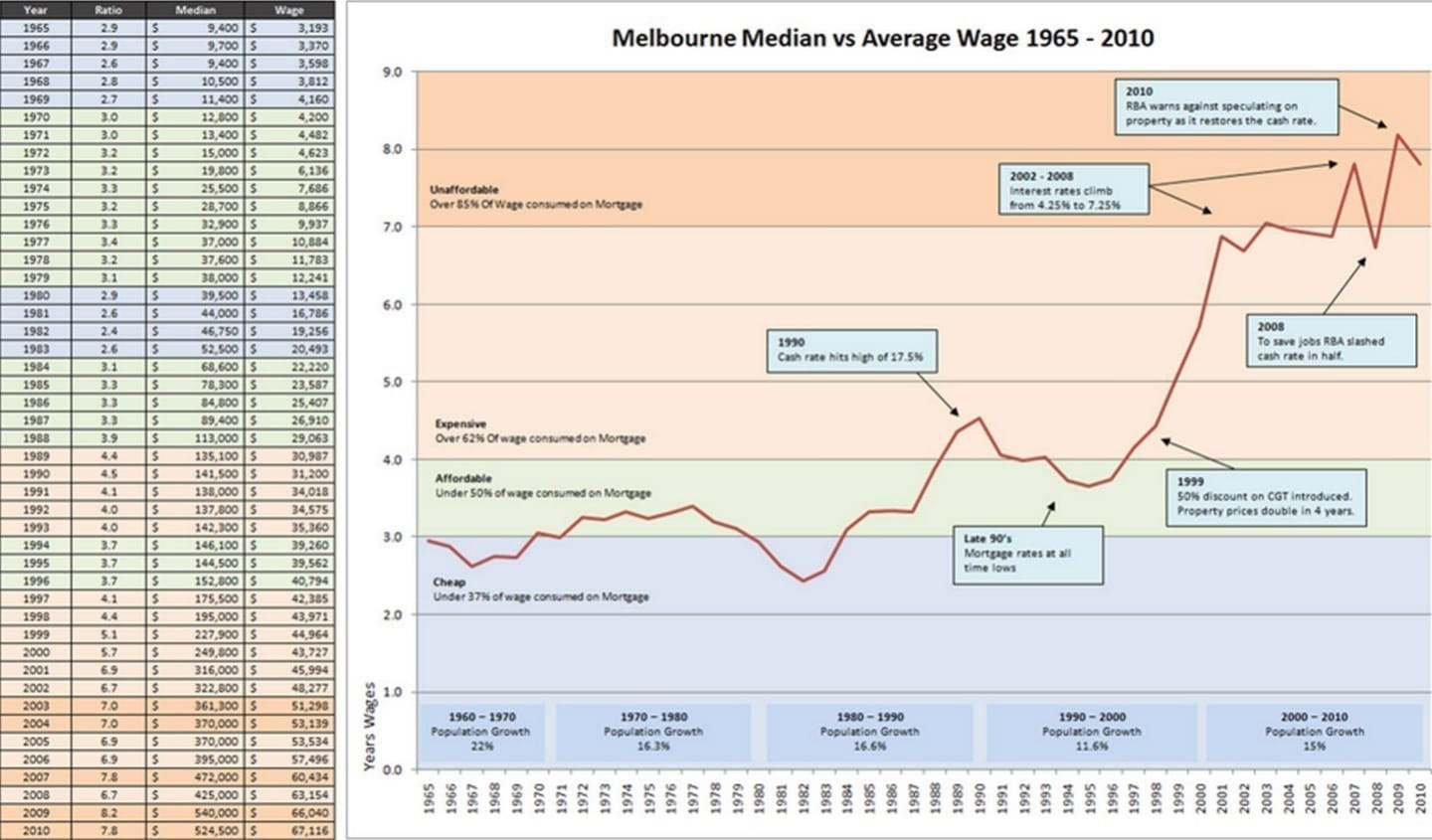

Click to open in new window:

Source: Bubble Economics by Paul D. Egan and Philip Soos

It used to be called ‘Monopoly’. Today its termed: ‘getting onto the property ladder’.

Retire as a renter or find a way to ‘work the system,’ playing a dangerous game of debt and leverage, and hoping when the wind finally blows, you’re not left holding the house of cards.

For those unable to afford current high prices, they will see no tax benefit - unless their income is low enough to require welfare assistance.

Rather they will be at the mercy of rising rents with an uncanny tendency to outpace inflation, tight vacancy rates and few low budget options.

If, as above, they are the ‘lucky’ beneficiaries of family assistance to enable their step onto the first rung of the ladder, they’ll enter a tax system skewed toward ownership, the benefits of which are capitalised into the price, pushing values higher.

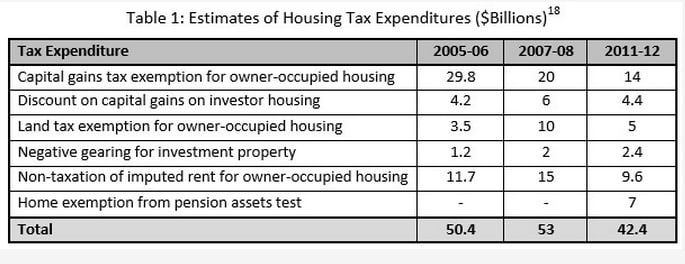

Source: Bubble Economics by Paul D. Egan and Philip Soos

Under such a system, the final consequences are set in stone.

On a global scale, the land bubble induced financial crisis of 2008 left millions suffering fatal burns.

Tough austerity measures that followed destroyed the hopes and dreams of thousands of Europe’s youth.

For those just entering retirement, savings were wiped away, along with any chance of employment in later years.

Australia escaped relatively unscathed, but this isn’t because we’ve solved the boom/bust cycle.

Our policies differ little from the affected countries that promote ownership with similar inflationary measures.

First time buyers have no memory of a recession and understandably want their share of the pie.

However our history is littered with recurrent patterns of boom-bust credit and asset bubbles, commonly triggered by high land prices.

They all heralded financial instability and dreadful social consequences - a study of which should perhaps feature higher on the school curriculum.

We’ve just entered into another cycle and already prices have exceeded previous peaks.

Housing cycles are long-term affairs, however unless we begin to studiously take measures to change our tax and supply policies, when the clock ticks round again – as it inevitably will – our house of cards will blow over like the rest.

Many applauded Malcolm Turnbull as he made the most of his share of publicity during the CEO sleep out last week, to raise money for the homeless.

However, Turnbull is part and parcel of a budget and government that exacerbates housing affordability, and by consequence, the very problems he endured a cold night to help ‘solve’.

This is because the government has structured the tax burden to fall predominantly on wages and productivity – which advantages those at the top, who see their landholdings increase way in excess of any taxation or earned income through no individual effort of their own, rather the collective efforts of community investment (items of which I’ve detailed previously) – whilst the productive earners at the bottom of the pile, struggle to make ends meet.

In other words, by hoarding housing, the rich pay less - the poor pay more.

Unless we restructure our tax and supply policies to address this and reduce land prices, encouraging instead individual investment into productivity rather than rising land values. Welfare measures to help the homeless are merely a Band-Aid to capture the increasing number falling foul of the system and never a cure.

Which brings me back to the one question both reporters failed to asked,

“Who are rising property prices good for?”