Looking at our housing market through foreign eyes

I had the good fortune to meet two investors from Dallas, Texas last week - visiting in part, to survey the Australian real estate terrain and in return, provide a unique opportunity to glimpse the madness of it all through foreign eyes.

A cursory look through the press paints a colourful picture for our visiting observers. Obviously, the spectacular rise in Sydney’s valuations has come under incredible scrutiny over the past 12 months or so.

Like any upswing in the property cycle, it’s been exacerbated by a mix of forces, culminating in a shortage of effective supply against a bull run of speculation, which all agree has an inevitable end by date and no doubt subsequent correction when the tide changes (‘when’ being the operative word.)

The latest stats from RP Data’s capital city Home Value Index for the first quarter of the 2014 have evidenced “a near record level of growth throughout the month of March” rising in excess of 2% coupled with an “ongoing escalation in housing finance commitments”.

Sydney dwelling values are now reportedly 15.8% higher than their previous peak, some distance from Melbourne, which shows a more ‘subdued’ 4.7% ‘post peak’ increase (movements, which in industry speak are neatly termed a ‘recovery’.)

In response, the RBA, are like a read blowing in the wind, employing the same old wooden tools they’ve always relied upon as they warn investors in their latest Financial Stability Review, - (like last year’s review, when stating how “undesirable” it would be “if households were to exhibit less prudent behaviour than they have over the past few years”) - that the:

“Cyclical upswing... cannot continue indefinitely” and any ease in lending rates holds the “potential to encourage speculative activity in the housing market”.

Community service groups hurriedly rush to Canberra, flagging a wealth inequality crisis, presenting yet another shandy of submissions to the rinse and repeat sequel of the last Senate inquiry into housing affordability,

And as Barclay’s Chief Economist Keiran Davies sounds the alarm, reporting household debt to disposable income has hit a record “177% peak”, the public outcry against foreign investment bidding up prices has prompted the Coalition’s conservative version - reminiscent of Kevin Rudd’s 2010 ‘1-800-I-SAW-AN-ASIAN-AT-AN-AUCTION’ debacle - to assess “what is happening on the ground” and stave off the growing concerns that seem to indicate rules are not being adhered to.

The analysis my two new friends from Texas would hear from economists in response to the above backdrop is equally schizophrenic.

Whilst the Governor of the RBA Glenn Stevens is telling audiences that a modest overheating in housing markets could have “long-term negative consequences for economic growth.” AMP’s chief economist Dr Shane Oliver is assuring the “normative” response to low interest rates producing a sharp surge in established house (land) prices, is “great news for the economy!”

According to Oliver, housing may show an “overvaluation criteria for a bubble,” but, we’re not in one yet, otherwise “property spruikers [would be] out in a big way” or “buyers rushing in for fear of missing out!”

Obviously Dr Oliver has not been attending many auctions or property seminars of late – otherwise he’d have plenty of evidence of the above practices (at least in the two biggest capitals.) They’re all but engraved into Australian culture.

Notwithstanding, Christopher Joye is back to the task of boosting his readership figures, evidencing the quite the opposite - warning overvalued prices could see “unprecedented 10 to 20% losses across the board” when/if the market 'normalises'.

Grave concerns indeed, albeit, it whistles the same tune as most industry commentary regarding affordability, with anxieties only going so far as to ensure an already inflated platform can be sustained (through prudent lending, of course) without open and strong advocacy into the policies that would stop these cyclical peaks and corrections, which result in numerous crash predictions, inevitable pain for new home buyers, a real wealth inequality crisis – for what seems to be for no more than generating publicity, whilst maintaining the status quo.

“Build more houses!”

Unfortunately, the assumption – both here, and overseas – remains, that the only way to make houses more affordable, is to increase the supply of new dwellings.

Building more accommodation seems like an easy prescriptive cure, with supply verses demand being a well-tested economic model – that is, until it comes to the land market.

We can’t seem to deliver this supply at normative prices for the locational price/distance trade off.

Speculative activity, further promoted by a constipated planning system, has resulted in ever increasing land values, on ever decreasing lot sizes.

Analysis by RP Data shows vacant land prices over the past 20 years, have lifted from a median rate of $76.47 per square metre, to $507.70 per square metre, as of the end of 2013. Whilst the average ‘lot’ size has dropped from 700 square metres, to 500 square metres – and in some states, less than 400 square metres over the same period.

Obviously reforms to the planning process would greatly assist, however contrary to common belief, it would not alone provide a cure.

To truly restore housing back to fair value, we would have to remove the level of speculation manufactured into the structural design of our housing market and this is one side of policy reform Government has repeatedly refused to address.

Speculation

To be clear, an increase in the natural price of land, is an expected result when economies are improving due - for example - to capital investment in infrastructure, as is the case in Australia currently, with Tony Abbot’s desire to be knighted the ‘Infrastructure Prime Minister.’

Infrastructure intensifies the use and demand for land as the population grows, assisting job creation and collaboration between individuals.

Therefore, taken alone, rising values should be a ‘good’ thing for our country – (and economy) – or at least they would be, if the gains truly benefitted the community.

Any manufactured improvement to a location’s public amenities, gifts a beneficial trade-off to the owner, who receives a windfall in remuneration as the resulting economic impact boosts productivity.

This increase in values is what economist’s term 'economic rent', although expressed rather misleadingly in popular vocabulary as capital growth.

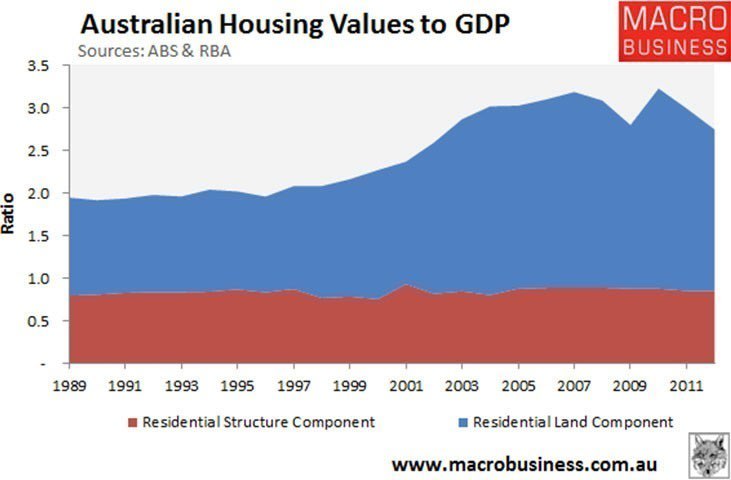

To clarify – capital infers something that can be reproduced through productive activity, however we know from housing data, that the true gain in house prices is really collected in the rising cost of land, which takes up a 4.1 trillion dollar share of our 5.02 trillion dollar housing market.

Land cannot be reproduced because it can’t be moved, it’s fixed in supply, and therefore any financial benefit derived from improving the surrounding facilities, is merely soaked into the ground.

This is why land banking is promoted within the industry as a popular investment strategy – although to be clear, it’s not investment at all.

Investment implies the creation of wealth, whereas speculating is a zero-sum game; the wealth is not created, the landowner does nothing – and for the homeowners in Australia, lucky enough to be situated close to the best seats in town, it’s a generous tax-free unearned windfall.

Unwontedly or not, land bankers who hold their underutilised plot in lieu of capital gains, are free loaders on the economy and building activity does not respond to demand, but is only boosted when values are assessed to be on an upward trajectory.

Policies such as negative gearing, depreciation, capital gain exemptions, the encouragement to acquire properties and gear against them in self managed super funds, as well as the use of the family home as a wealth reserve for retirement, enforces speculation into the foundational makeup of our property market.

Land cycles

But I’m not informing Australian’s of anything they don’t already know. People have become acclimatised to property being expensive, and our housing has become expensive because its value is derived from its accumulated and speculated future capital gains - correctly termed economic rent.

According statistics, home buyers typically move every 10 years or so. The price they are prepared to pay, is balanced against the price they expect to achieve, minus expenses – and in all my years assisting buyers, (barring the odd downsizer) I have never met a single one who calculated otherwise.

This is why property cycles – this is what promotes speculation.

The banking sector, which has a monopoly on this process (after all, how many can purchase a property without a mortgage?) increases the volatility of this cycle markedly, however banks, lending, money (credit) creation, lack of regulation does not cause the cycle, (or stop the cycle). Speculation does.

We had land booms and busts before the evolution of our modern banking system – and without a change to the structural makeup of our housing market, we’ll continue to have them.

Lending restrictions can mitigate risk, but due to the vested interests of banking system, it will not remove it to the degree needed to stop the cyclical impacts.

Easy Earnings

Notwithstanding, for those home owners and investors who purchased over the last decade or so, making money through buying, holding and acquiring property (land) has been a far more effective in accumulating wealth by way of earning income and channelling it it into productive activities.

The BRW rich list is littered with examples, and for those who are not involved in the business of property, land is where they invest their dollars.

Of course, for the first home buyer on a single wage priced out – the mantra resumes that we just need to build more dwellings, the process of which contains just as much speculative activity in its design (including how we fund for infrastructure) so as to exacerbate the problem.

But how does it look to our Texan friends?

Well let’s just say, they’re not rushing to move here.

Texas is one of the top locations for interstate migration in America.

As with Australia, the economy has been super charged by way of a commodity boom, but unlike Australia, industries such as tech, manufacturing and business services are thriving and hiring in droves.

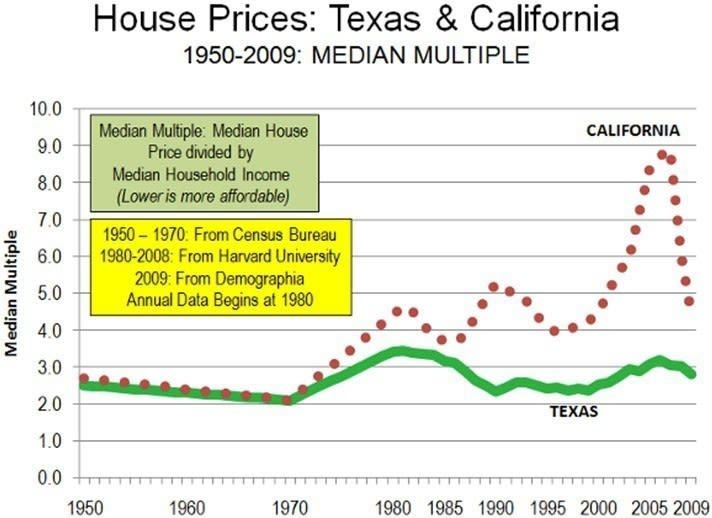

The expansive list my new Texan friend’s reeled off, highlighting the number of companies moving their central operations into the state (rather than ‘offshore’ as they do here) is impressive, and when I asked how much they would spend purchasing a ‘home’ I was told that “three times annual earnings” would buy the best in town, which was summed up by the comment “like the house my parent’s own”.

Most of the units and condos in Texas are rentals – owned by large investment funds for example, and used as a hedge against inflation and source of positive cash flow.

There are less family sized rentals (detached dwellings) albeit, because housing is affordable, there is also less demand.

Devoting earnings to building a property investment portfolio isn’t a consideration for most Texan residents.

The state didn’t experience a housing bust, because it didn’t experience a housing boom.

The subprime crisis didn’t hit, because speculation was removed.

This was in part due to liberal and well funded supply policy, which ensures housing is built on demand and essential infrastructure funded by way of a deductable municipal utility district tax, administered by residents, funded by a bond, and payed back proportionally over a lengthy period of time.

The additional key however in what’s been termed the “Texas miracle” is low taxes on productivity, lack of state income tax and a good regulatory environment, offset by higher than average property tax.

It’s not perfect – Texas does not remove other taxes, such as sales tax, which has a destructive impact on commerce – and property is taxed as well as land (where as ideally, in a truly productive environment, only the unimproved value of land – the economic rent – should be subject to a tax, which is far easier to accurately assess than the total capital improved value). However it makes the point.

Whilst Texas boosts and attracts productivity with lower taxes, discouraging speculation in the areas that destroy it, Australia leans to the opposite.

We’re not immune to real estate crashes and there is plenty of evidence to prove their increased severity when prices are allowed to escalate. But, the best way to mitigate the risk and protect against volatility, is to encourage the industries that advantage the working population most (manufacturing for example) and take the air out of those that advantage land speculators the most.