Subjectivity, damned subjectivity and housing statistics

Guest observation

In a recent article on Property Observer (Lies, damned lies and housing statistics) commentator Arek Drozda discusses Australian property statistics. He tells the reader many commentators write stories around property numbers that can't be relied on.

Drozda claims that "data does not lie". However, data is just a collection of facts and statistics for reference or analysis and, as Janine Skorsky of House of Cards says, "There is no arrangement of facts that is purely objective."

Drozda provides his own narrative around the data he uses in the article, as I do in any article I write (including this one). We are all human, we all experience different events over our lives that shape how we see the world, how we interpret things and so when we go to present data or share an opinion, it is always loaded with that bias.

To suggest that data can't be manipulated to fit various views is disingenuous. Data can be made to lie in various ways, for example in it's initial collection (biased sampling), through its visualization (how it's presented to the reader) or by using it selectively.

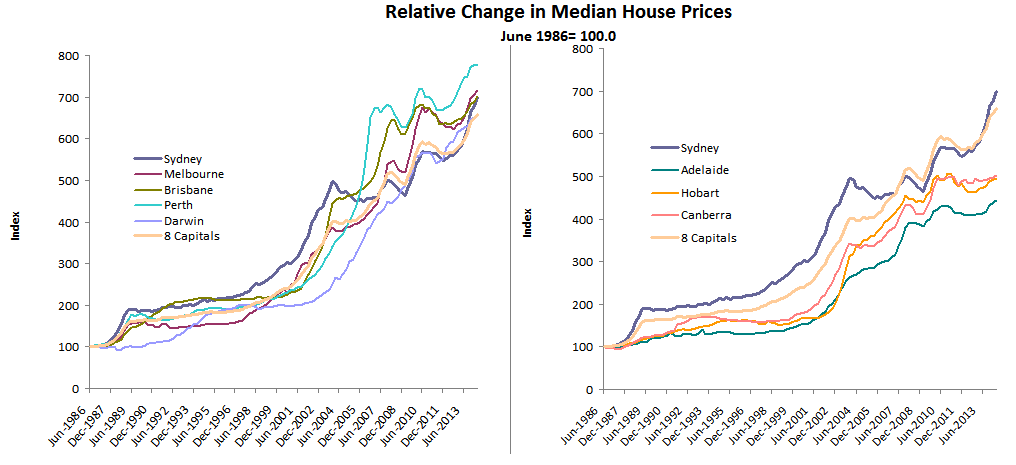

Drozda uses his narrow selection of data to try and show that Sydney property is not suffering from rampant speculation as it's only "catching up" to the other capital cities:

Source: Arek Drozda using ABS statistics

But presenting data like this can be used to mislead as there is no supporting evidence provided to show that the cities were equally valued (relative to each other) at the point the data starts, despite his insistence that the capital city median prices "being in a tight range" during the mid 1980s suggests they were.

Drozda has used data to support his opinion that Sydney is not experiencing a high level of speculation or is overvalued, but it's the data he leaves out of his story that suggests it could be otherwise. For example rental yields are lowest in Sydney and Melbourne, substantially lower than in the rest of Australia.

Source: Residex

Other data that suggests Sydney (and Melbourne) are seeing a higher level of speculation and overvaluation relative to the rest of the capitals includes investor finance which has soared (via Pete Wargent).

Source: Pete Wargent

The above chart is not indexed (and is state rather than capital), but it's clear that New South Wales and Victoria are experiencing a greater level of speculation with rolling investor loans far higher than their previous nominal peaks, whilst the other states barely tread water.

I could go on with other examples indicating a higher level of speculation in Sydney, but the above does well enough given the limited content of the article it was addressing. Of course the above is my view based on the data available. Have a look at Drozda's presentation of the data and mine, and make up your own mind.

This article continues on the next page. Please click below.

When I queried (on Twitter) another of the charts Drozda had presented purporting to show Sydney (and Australia) having relatively "affordable" property (below), he pointed me toward an older post where he explained his position in more detail.

Source: Arek Drozda

In this article Drozda dismisses "simple" ratios of prices-to-rents or prices to household disposable incomes and instead presents his own simple argument that when it comes to affordability price doesn't matter, only serviceability (and interest only at that).

He says that principal is omitted because it's savings:

"Paying off the loan principal is omitted in the analysis since it equates to savings and is therefore deemed irrelevant (i.e. every dollar that is paid off becomes owner’s equity that can be drawn upon in the future)."

The claim is preposterous, given that these "savings" have to be borrowed back (with interest payable) or only retrieved in full by selling the property.

Drozda writes about a metric referred to as the "cost of buying", which measures only the cost of interest on the loan and then uses that as his basis of "housing affordability". As I've only recently written on this topic, I'll quote from my previous piece (Why Serviceability ≠ Affordability):

"Even if interest rates had remained elevated the entire period of the loan, it still ends up more affordable over the long run to have double the interest rate, but lower price to income ratio. Not only that but it would be faster to save the deposit given that it's a lower amount (relative to income) and I haven't taken into account the higher interest rate on saving for the deposit which would have benefited the 1992 scenario.

"Costs such as stamp duty which are tied to the price paid would be lower too. Finally, higher interest rates tend to come with a higher rate of inflation, so the real value of the debt would be reduced faster as wages increased, meaning the buyer in 1992 would have found it easier to ramp up the level of repayment.

"...When considering affordability, we need to take a holistic approach and not use a simple snapshot of a single repayment as the basis to make judgement calls on whether house prices or a mortgage used to purchase them is affordable. A mortgage is a long term commitment and shouldn't be treated so trivially by market commentators."

Drozda's argument in this article does show how buyers have been able to service mortgages at these higher prices (as he puts it, "rediscovered their true financial capacity"), mostly a result of "structurally" lower interest rates, but as I've shown that doesn't make them affordable unless you're of the opinion that serviceability is the same as affordability.

He finishes the article on this note:

"We can afford current prices – and we can afford them more than in 1986. The only hurdle is that it requires accepting a level of debt that many may not feel comfortable with."

It's clear that Drozda is devoted to the first rather than second definition of 'afford' below:

Afford: To have the financial means for; bear the cost of.

Afford: To manage or bear without disadvantage or risk to oneself.

The data he presents is shaped to support this angle.

Is it a lie? Well I guess that's subjective. I'll leave it for the reader to decide.