Australian real estate: Once again ticking boxes for foreign investors

A few days ago, I was asked to comment on The Candy GPS Report which identifies 12 future cities for real estate investment – one of which is Melbourne.

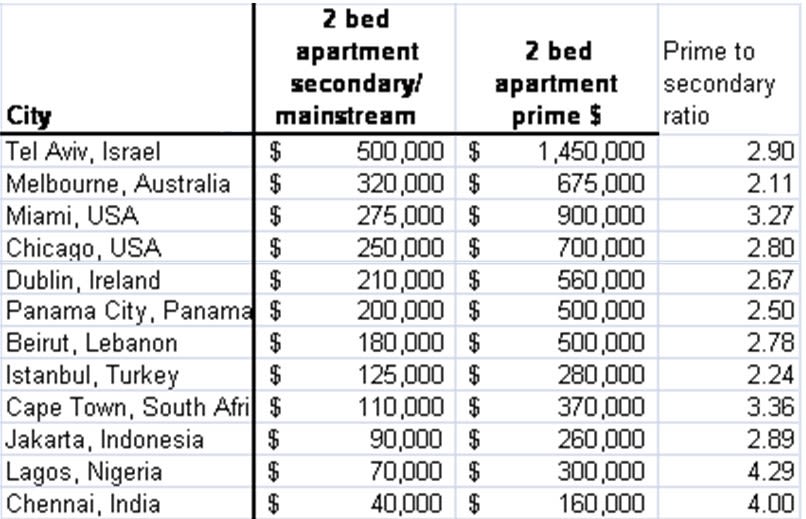

The 12 cities are as follows (from most expensive to the least):

Just in case anyone is still deluded that we build the accommodation for people to live in. It correctly outlines how real estate is progressively becoming a mainstream asset class for investors.

Ultra high net worth individuals from Germany, the United States, Japan and other parts of Asia are now looking at secondary markets and second tier cities as an alternative to the somewhat bubbly established safe havens of London and New York.

It comes on the back of what is already a fraught subject in Australia; the impression that “foreigners” are purchasing our residential real estate – bidding up prices and forcing out first home buyers who simply can’t compete.

The parliamentary inquiry last week was devised to put this matter to rest, to prove it isn’t so. Although, for those in the industry who work directly with buyers and sellers, it merely confirmed what we already know.

Australia has a largely unaudited system of ‘non-resident’ investment in its real estate market.

Whilst the official figures seem to demonstrate the larger proportion of demand is increasing supply rather than inflating values. With only eight staff to audit the thousands of applications the FIRB receives, it admits it relies on "honesty and stern speech", whilst those who work on the ground within the industry, rightly attest that there are loopholes in the rules.

For example, corporations, friends, family members, relatives, and solicitors are all able to purchase for those who do not quality - and from anecdotal evidence alone, they seemingly do.

Importantly, it is not up to real estate agents to report their suspicions and inflame a debate which has bordered on racist against our Asian migrants.

The process must be correctly audited, and until it is, argument will continue. However, we should not let this mask the real issue surrounding our residential real estate market – that of government policy.

As the RBA recently noted in their “wouldn’t it be nice to have houses at affordable prices” speech a few weeks ago, conditions are not only hard for first time buyers, with wages tracking below the rate of inflation whilst prices trend higher, many others are falling through the cracks altogether.

Previous reports have shown fewer younger and middle-aged people own their own home and across all age groups, fewer own outright. There has been an increase in both the number of people recorded as homeless as well as the number living in other marginal housing.

If Australians in 2011 had the housing consumption patterns they had in 2001, they would occupy an additional 284,000 dwellings. Instead, despite families having fewer children and an aging population, we’ve seen a reversal of the decade-long decline in household size, which outside of any cultural shift, clearly points towards pressures of affordability.

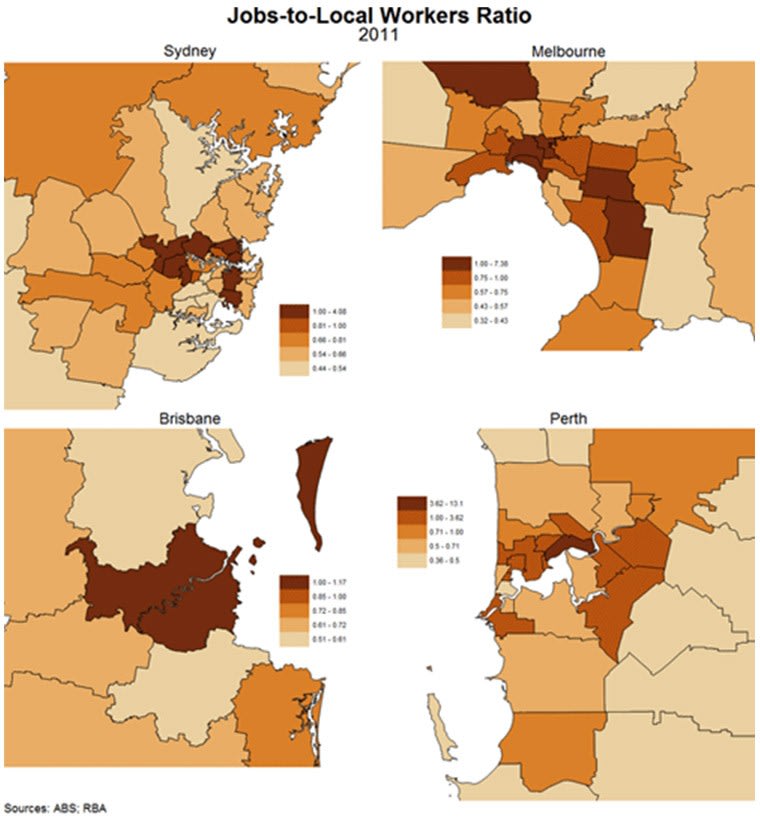

Now new buyers risk not only being locked out altogether, but also (as the RBA’s Lucy Ellis puts it) “where the jobs are and where the employed people live” – which remains around the central areas of our largest capital cities. As the speech demonstrates, we have not decentralised – in fact quite the reverse.

It comes down to the same old issue – housing policy.

This article continues on the next page. Please click below.

We build for an investor market in a lopsided economy that has pinned itself to rising land values to support every other area of investment.

This is great for those who were lucky enough get in at the beginning of the lending boom, many of which now have an ample welfare pot for retirement.

Not so great for first home buyers today who are struggling to afford, well… anything at all.

The many vested interests from politicians to industrial lobbyists, to keep land prices inflated, can be evidenced in every area of real estate policy.

From our failure to correctly audit the investment market (foreign or otherwise), to other matters such as first home buyer grants, tax breaks for investors, turning a blind eye to spruiking, a failure to enforce strong lending rules, and a continual inability to supply affordable housing in the fringe localities on what should be dirt cheap land (close to its agricultural value), enabling new buyers to purchase at no more than three times annual income.

Instead we unduly inflate prices in the outer suburbs through a process of ‘false scarcity’ produced by urban boundaries, zoning regulations, onerous development taxes and infrastructure overlays, all of which encourage speculation in vacant land, which is becoming a far more lucrative venture than building for current low yields.

This further inflates land values in the inner and middle ring localities because, as anyone familiar with classical economics knows, it’s the fringe cost of land that sets the base price for the suburbs closer in.

The report by The Candy GPS mentioned above, which promotes the potential for Australian real estate investment, mirrors other assessments with similar conclusions.

For example, in a study by investment bank Credit Suisse earlier this year, it correctly asserted:

“The marginal buyer of Sydney and Melbourne real estate has changed, as have the drivers of property prices.”

It points out a potential $44 billion investment into Australian residential real estate over the next seven years, mainly due to our geographical advantage in the wider Asia-Pacific region.

To put this into context, by 2025 the Asian region will account for almost half of the world’s output and also be the world’s largest consumer.

In Julia Gillard's ‘Asian Century’ speech, she asserted:

“We are now seeing the most profound rebalancing of global wealth and power in the period since the United States emerged as a major power in the world.”

The number of Asian students studying here is at record highs.Trade flows, research and business development, education, tourism, and increased levels of migration have given us the potential to capitalise on the inflow. And as the capitals of the two states with largest recorded arrivals of Indian and Chinese migrants, Melbourne and Sydney are set to advantage.

The trouble of course, comes down to management. The influx will push prices higher and not benefit us over the long-term (especially the next generation of priced out buyers) unless we change policy.

If we were really smart, we would look at our system of taxation to ensure this investment in land is not only sustainable – but also advantageous to the broader economy.

To do this, we should work on a long-term sustainable plan to remove an array of bad taxes, including stamp duty which impedes housing turnover and labour mobility for owners seeking alternative employment opportunities, trapping residents in housing. As well as phasing out other policies, which focus investor demand on established real estate rather than the construction of new supply – such as negative gearing for example. Instead we should replace them all with a broad based tax on the unimproved revenue from the locational value of land alone – not the buildings on top.

Currently, we assess rates on the combined value of both – which means for every improvement to the capital (the man made asset on top) we place a penalty on building activities which impedes the productive capacity locked in our land market.

An effective land value charge, as well as shifting ‘bad’ taxes from productivity, would result in a number of changes.

It would encourage effective utilisation of land in both inner and outer suburban districts, stimulate construction, take some of the speculative element out of the land market, reduce prices and thereby assisting with decentralisation. And with less with ‘economic rent’ locked in the soil, over the longer term would act to increase – not decrease wages.

Combine this with an overhaul of supply policy and the accumulated wealth being brought into the country could be channelled into productive activities, rather than rampant real estate speculation.

It's unlikely that this will occur however. History attests that governments have a habit of allowing wealth to trickle up, not down – usually due to a combination of ignorance, lobbying and vested interests. Albeit, if policy fails to change through both taxation and supply, at some point prices will get too high for productivity to sustain and as recent international examples attest, the future consequences of this will be significant.