More hospitals will not cure Australia’s ailing health-care system. There’s a more efficient way

GUEST OBSERVATION

The federal government has just promised to increase spending on public hospitals from A$21.7 billion in 2018 to A$26.2 billion by 2023. Expect more hospital promises in coming weeks. There is a long history of parties at both state and federal level pledging new hospitals during election campaigns.

Building new hospitals may at first seem sensible, especially as the population grows. But it will not cure the health system’s most pressing ailment. Instead, our research shows it’s more effective to focus health policy on people and prevention.

A problem of demand

It is true that hospitals in Australia aren’t keeping up with demand. Though supply of beds has increased, the population is growing while also ageing. This is increasing demand for all health-care services, including hospital beds.

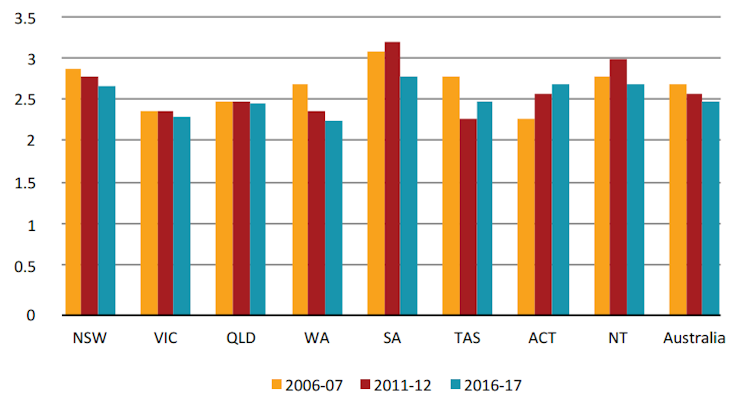

The following graph shows the change in the number of beds per 1,000 people in all states and territories since 2006. Only in the Australian Capital Territory has the ratio improved.

Available hospital beds per 1000 population, by region, public hospitals (including psychiatric). Bankwest Curtin Economic Centre | AIHA (various years), Australian hospital statistics, Health Services Series; AIHW (various years), hospital resources' Australian hospital statistics, Health services series.

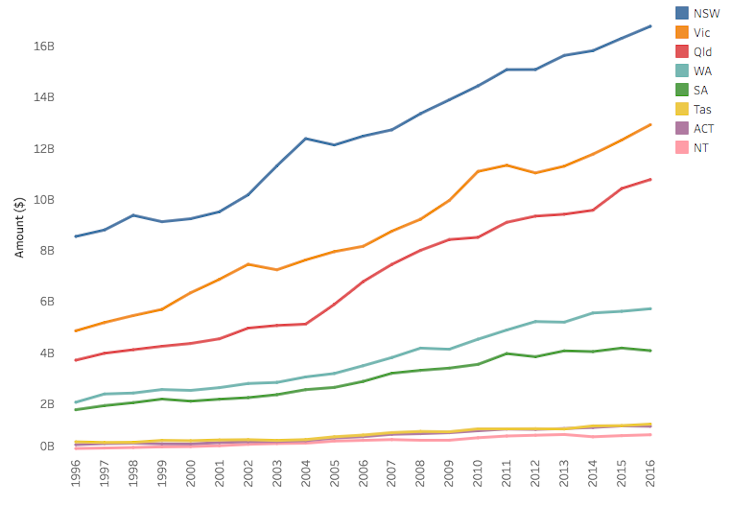

State and federal governments thus feel a lot of pressure to spend more on hospitals. In 2016-2017 it was $69 billion Australia-wide – $2 billion more than the previous year. The following graph shows expenditure on public hospitals by state over the past two decades.

Public hospital spending in each state since 1996. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, CC BY

Queensland shows the greatest growth over the past two decades. In Western Australia, where we did our research, the proportion of government health budgets spent on public hospitals rose from 26% to 31%.

Preventive measures

We looked at why the hospital care is growing faster than the overall health sector, and what can be done about this.

Our conclusion: there needs to be more focus on the “unsexy” parts of the health-care system that treat people before they get sick enough to need a hospital. Prevention is cheaper and more effective than cure.

For example, it is estimated that A$9 million invested in anti-smoking campaigns between 1997 and 2007 saved A$740 million on smoking-related illnesses like lung cancer.

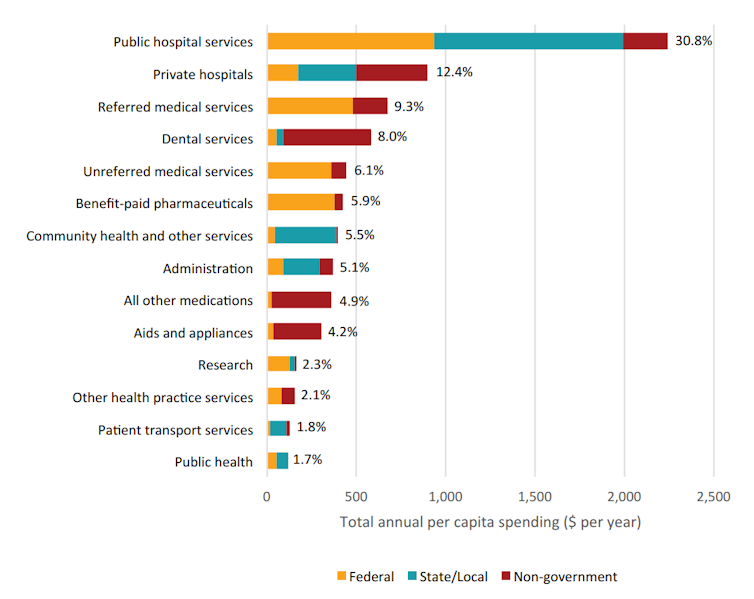

Yet our breakdown of health spending in Western Australia shows just 1.7% is spent on preventive measures – called “public health spending”. Australia-wide the average percentage is even less, according to research from La Trobe University and the Australian Preventative Partnership Centre.

Breakdown of health care spending in WA. Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre | Authors’ calculations from AIHW health expenditure database.

Early medical attention is another way to reduce the need for hospitals. In analysing data from around Western Australia between 2009 and 2016, we generally found that increasing visits to general practitioners reduced the incidence of avoidable deaths (deaths that could have been avoided with better treatment or prevention).

People-centred approach

Limited prevention and early detection comes back to the way we fund health care. Australia’s health system is funded using a “hospital-centred” rather than “people-centred” approach.

This means hospitals are funded by the number of patients cared for and the type of procedures done. Hospital and GPs are funded separately. There is no incentive to cooperate and keep people out of hospitals.

A people-centred approach, on the other hand, would give funds based on patients’ health outcomes, rather than their particular treatments. GPs would be paid to manage patients, with the goal of keeping them out of hospital.

This system would particularly help people living in remote and rural regions, including Indigenous Australians, who are disadvantaged by the relative lack of resources being spent on local and preventive health.

The Canterbury model

The Canterbury region in New Zealand. English Wiki

The best example of such a people-centred system is New Zealand’s Canterbury model – named after the Canterbury region on New Zealand’s South Island (which includes Christchurch).

Instead of separate budgets for GPs and hospitals, Canterbury created a “one system, one budget” approach. This led to new programs that weren’t possible under the old system. An example is Healthpathways, which brought together GPs and specialists to decide on treatement programs for individual patients.

In working to make hospitals the last resort, more time and resources have gone to GPs. There are now more 24-hour clinics, for example, making it easier to get treated by a local doctor when needed.

A study of the Canterbury system showed that between 2007 and 2014 the number of people being hospitalised declined from 6.59 to 5.83 per 1,000. While an 11% decline may not seem huge, it represents a significant financial saving, given the high cost of hospitalisation.

Canterbury shows what can be achieved by rethinking how health care funding works. Australia has the opportunity to reimagine its health care system in a similar way.

New hospitals get a lot of attention. Politicians can point to them as concrete evidence they’re doing something to help. But emphasising hospitals as the most important part of the health system comes at a cost, and will only get more so as the population ages.

It’s time to discuss alternatives. Putting more resources into prevention and people is the right medicine for our future health needs.![]()

Steven Bond-Smith, Research Fellow, Bankwest-Curtin Economics Centre, Curtin University

Alan Duncan, Director, Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre and Bankwest Research Chair in Economic Policy, Curtin University

Astghik Mavisakalyan, Associate professor, Curtin University

Yashar Tarverdi, Research fellow, Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.