Is Perth really running out of water? Well, yes and no: Don McFarlane

GUEST OBSERVER

As Cape Town counts down to “day zero” and the prospect of its taps being turned off, there have inevitably been questions about whether the same fate might befall a major Australian city. The most striking parallels have been drawn with Perth – unsurprisingly, given its drying climate, rising evaporation rates (which increase consumption and reduce water yields) and growing population.

So is Perth really running out of water? The answer depends on what type of water is being considered, and what constitutes “running out”.

When faced with this question most people think of drinking water, which is of course essential for household use.

It often ignores non-potable groundwater that is heavily relied upon in Perth to irrigate gardens, lawns, ovals, golf courses and market gardens. This water is also used by light and heavy industry, as well as being crucial to the health of wetlands and vegetation across the coastal plain.

Lake Jualbup in Perth’s western suburbs showing periods of low and high water level. Photos by Geoffrey Dean. saveourjewel.org, Author provided

Perth’s drinking water supplies are largely safe, thanks to early investment in the use of groundwater and in technologies such as desalination. But somewhat ironically, as this recent book chapter explains, the future supply of lower-quality water for irrigation and to support ecosystems looks far less assured.

A drying climate

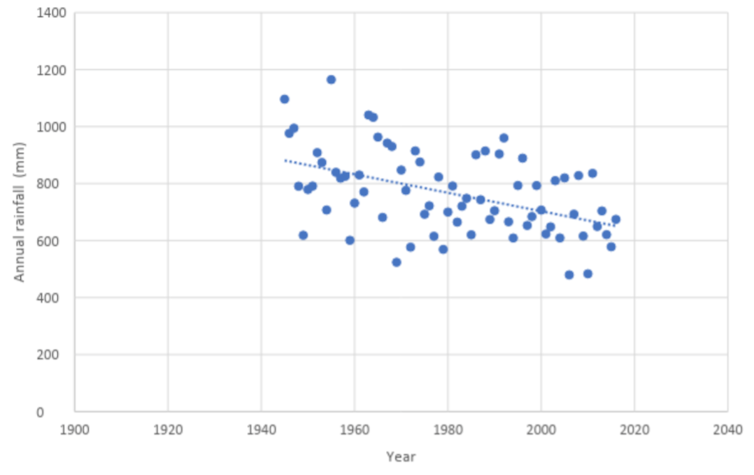

Perth’s annual rainfall has been declining by about 3mm per year on average, while the number of months receiving at least 200mm of rain has halved. Meanwhile, the annual mean temperature anomaly has increased by 1℃ in southwest Western Australia in the past 40 years and possibly by more in Perth, given the urban heat island effect.

Perth’s rainfall trend, as measured at Perth Airport’s rain gauge. Bureau of Meteorology

The overall effect is that soils and vegetation are often dry, meaning that rainfall will be lost to evapotranspiration rather than running off into rivers and dams, or recharging underground aquifers.

At the same time, Perth has made major changes to its drinking water supply. The city now relies chiefly on groundwater and desalination rather than dams. For a variety of reasons, drinking water use per person has declined, most notably since the early 2000s when sprinkler restrictions were introduced. Some have switched to self-supply sources such as backyard bores, so for them total water use may even have increased.

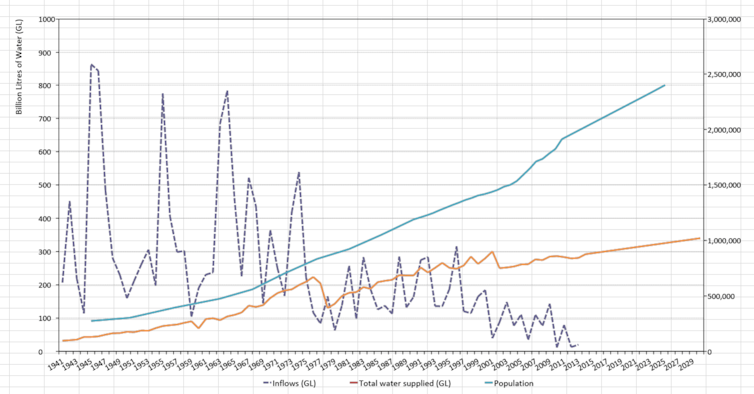

Perth’s trends in runoff, population, and water supply. Water Corporation

The reduction in per capita use of drinking water is just as well, because inflows into Perth dams have fallen from 300 billion litres a year to less than 50 billion. This disproportionate drop in stream flows, even against the backdrop of declining rainfall, means that evaporation from reservoirs can exceed inflows in very dry years.

Since the late 1970s, Perth has increasingly used groundwater rather than dam water. Seawater desalination has also grown to almost half of total supply. Even more recently Perth began trialling a groundwater replenishment scheme to recharge aquifers with treated wastewater.

With the declines in rainfall and streamflow predicted to continue, water security will continue to be an important policy issue over the next few decades. Although both are much more expensive than dam water, desalination and groundwater replenishment look set to secure Perth’s drinking supply, because seawater is virtually unlimited, and wastewater availability increases in line with the city’s growth.

Why are non-drinking water supplies less secure?

Boosting drinking water supplies with desalination or groundwater replenishment is unlikely to resolve the pressures on non-potable supplies. To understand why, it is necessary to understand Perth’s unusual hydrology.

Most of Perth is built on permeable sand dunes, which can soak up even the heaviest rainfall. This allows runoff from roofs and roads to be directed into nearby soak wells and absorption basins.

As well as cheap disposal of stormwater, the sands provide Perth with a place to store excess water from winter rains, which is then relied upon for summer irrigation. As a result, local governments have been able to provide many irrigated parks and sports ovals, and more than a quarter of Perth households use a private bore to water their gardens.

This arrangement isn’t as sustainable as it once was. Groundwater levels are falling under many parts of Perth, forcing the state government to reduce allocations and to introduce a range of water-saving measures such as winter sprinkler bans.

Unlike dam inflows, we don’t yet know the full scale of the reduction in natural groundwater recharge rates. But the question still remains: what can we do to halt the decline of this important water store, particularly as Perth’s population is expected to grow to 3.5 million by 2050?

About 70% of local road runoff and half of roof runoff already recharges the shallow unconfined aquifer, because it is the cheapest way to dispose of excess water in areas with sandy soils. As well as reducing discharge costs, this practice helps to ensure that bores do not run dry in summer.

Perth also has large main drains that are designed to lower groundwater levels in swampy areas and prevent inundation. Some of these waters could be redirected into the aquifer where there is a suitable site.

Don’t waste wastewater

About 140 billion litres of treated wastewater are discharged into the ocean every year in the Perth-Peel region. A further 7 billion litres are infiltrated into the sands as a means of disposal where there isn’t an option for ocean outfall. Recent investigations of these land disposal sites have shown them to be effective in protecting wetlands from drying and providing water for public and private irrigation.

Investigations have also shown that the quality of treated wastewater can be greatly improved when infiltrated through the yellow sands into the limestone aquifer in the western part of Perth. It is suitable for irrigation after a few weeks’ residence within the aquifer.

Without these kinds of measures, local governments will struggle to water parks and sports ovals, to protect Perth’s remaining wetlands, and to safeguard the trees that help keep us cool.

![]() So while drinking water supplies for an affluent city like Perth are reasonably secure, our vital non-drinking water supplies need to be augmented using some of the water we currently discharge into the ocean. As Perth gets even hotter and drier, and green spaces and wetlands are needed to provide much-needed cooling, we can no longer afford to let any water go to waste.

So while drinking water supplies for an affluent city like Perth are reasonably secure, our vital non-drinking water supplies need to be augmented using some of the water we currently discharge into the ocean. As Perth gets even hotter and drier, and green spaces and wetlands are needed to provide much-needed cooling, we can no longer afford to let any water go to waste.

Don McFarlane, Adjunct professor, University of Western Australia

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.