The story of skyscraper hubris – pride before a fall

"Bill, how high can you make it so that it won't fall down?" reportedly asked financier John J. Raskob, as he pulled out a thick pencil from his drawer, and held it up to William F. Lamb, the architect he had employed to design and construct The Empire State Building.

It was the ‘race to the sky’ and it marked the peak of the 'Roaring Twenties'. Capturing what is perhaps one of the most exciting periods in New York’s history.

"Never before have such fortunes been made overnight by so many people," said American journalist and Statesman Edwin LeFevre.

While areas of the economy such as agriculture and farming, were still struggling to gain ground from the post WWI depression, and a large proportion of the population continued to live in relative poverty. Advances in technology, rapid urbanisation and mass advertising accelerating consumer demand, produced an era of such sustained economic prosperity, it led Irving Fischer one of America’s ‘greatest mathematical economists’ to famously conclude that: "Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau."

“Only the hardiest spoilsports rose to protest that the wild and unchecked speculative fever might be bad for the country,” wrote historian Paul Sann in his publication The Lawless decade. “The money lay in stacks in Wall Street, waiting to be picked up. You had to be an awful deadhead not to go get some.”

Land values of course captured the gains, and between 1921 and 1929 lending on real estate increased by 179%, and urban prices more than doubled.

According to research collated by Professor Tom Nicholas and Anna Scherbina at the Harvard Business School in Boston, by 1930 values in Manhattan, including the total value of building plans, contained “only slightly less than 10% of the total for 310 United States cities (Manhattan included) during the same period”.

A staggering figure considering Manhattan at the time contained only 1.5% of the US population.

Few raised concerns however.

It was believed the Federal Reserve Act, created in 1913 “to furnish an elastic currency” would tame the business cycle and - as the First Chairman of the Federal Reserve Charles S Hamlin put it: “Relegate to its proper place, the museum of antiquities - the panic generated by distrust in our banking system.”

The national bank runs of the past had been exacerbated because there was ‘no stretch’ in times of crisis, or moderation in the rates of interest.

However, the bulk of lending against real estate over this period was not limited to New York, or to institutions that were members of the Federal Reserve.

Thousands of new banks were setting themselves up in outlying areas and as noted by Elmus Wicker, author of The Banking Panics of the Great Depression, “(they) were either operated by real estate promoters or exhibited excess enthusiasm to finance a local real estate boom”.

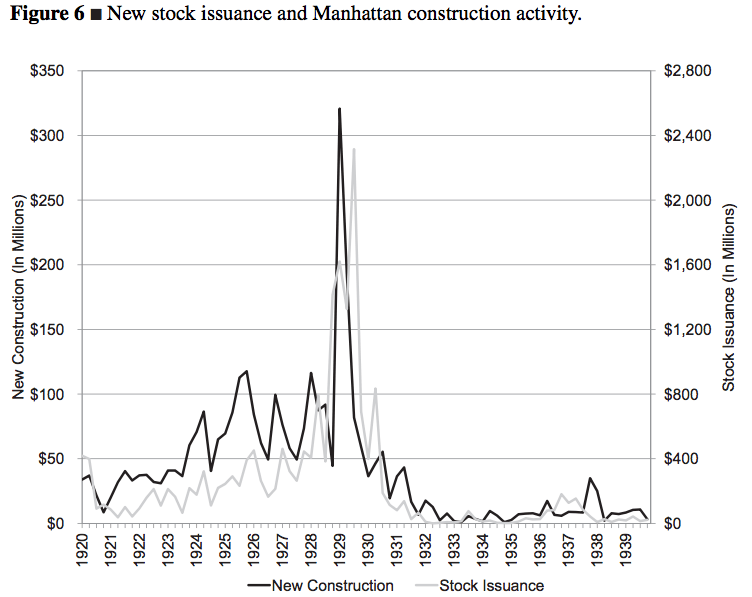

It brought with it a period of high inflation, and coupled with speculation in real estate securities, produced an explosion in the value of construction that would not be equalled until the boom and bust era of the late 1980s.

Source: Tom Nicholas and Anna Scherbina - Real Estate Prices During the Roaring Twenties and the Great Depression.

By 1925 real estate bond issues accounted for almost one quarter of all the corporate debt supplied - and between 1925 and 1929 alone, a quarter of New York’s financial district was rebuilt and 17,000,000 square feet of new office-space added.

This, prompted the owners of the grand Waldorf-Astoria Hotel at 34th Street and Fifth Avenue to sell.

Arising from a family feud between two competing cousins, the iconic guesthouse had been built at the top of a preceding boom and bust land cycle in the early 1890’s, and as ‘the most luxurious hotel in the world’ stood 17 stories high towering above the surrounding residences.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Article continues on the next page. Please click below.

By the late 1920s however, the décor had become dated and the social elite had centred themselves much further north.

The owner’s decision to upgrade into the Park Avenue district, and build what was then, ‘the tallest hotel in the world’ allowed John J. Raskob to acquire the site for The Empire State Building, for the not so small sum of $16 million.

Raskob needed a further $50 million for construction, which he achieved by way of a $27.5 million dollar mortgage, as well as engaging with a limited number of substantial backers.

“If the amounts seem considerable the backers knew that this was a money maker. The building would be the greatest showcase in the city filled with them. And tenants would line up to print “Empire State Building” on their letterhead," wrote Robert A. Slayton author of Empire Statesman: The Rise and Redemption of Al Smith.

The location was later criticised for being too far from public transport, but no such concerns were raised at the time.

New York office leases began on 14 May - the sooner the building was completed, the sooner it would bring in an income and notwithstanding, Raskob’s two main competitors also in the race for height supremacy - auto industry giant Walter Chrysler and investment banker George Ohrstrom - had already commenced.

Chrysler had seized his opportunity when gratuitous plans for an opulent office block designed by architect William Van Alen had fallen through due to financing.

He took over the project with clear intentions.

Adjusting the tower’s ascetics to reflect the company’s triumphs, with gargoyles, eagles and corner ornaments made to look like the brand’s 1929 radiator caps. Chrysler instructed the builders to make sure his toilet was ‘the highest in Manhattan’ so he could look down and as one observer put it, "shit on Henry Ford and the rest of the world".

Around the same time, George Ohrstrom, also determined to set the record, purchased the site that was to become the headquarters of The Bank of Manhattan at 40 Wall St (now the Trump Tower.)

Ohrstrom’s architect was H. Craig Severance, former partner and competitor to Walter Chrysler’s designer, Van Alen - and the bitter rivalry between the two added considerably to the dynamic.

Construction for 40 Wall St start started in May 1929 and no less than one month later, in April of the same year, fearing the competition Chrysler reportedly called his architect in frustration exclaiming:

"Van, you’ve just got to get up and do something. It looks as if we’re not going to be the highest after all. Think up something! Your valves need grinding. There's a knock in you somewhere. Speed up your carburettor. Go to it!" wrote Neal Bascomb.

Van Alen subsequently increased the height of the Chrysler tower to 925 feet, and added more stories - 72 in total.

Not to be outdone however, Severance added 4 extra floors to his own design, extending the building’s height to 927-feet – only marginally taller than Van Alen’s efforts, but by this stage the steel frame for the Chrysler building had already been completed and in Ohrstrom’s mind, he had already won.

The Bank of Manhattan was finished at record speed, taking just 93 days in total - meeting the 1 May deadline and setting the record for skyscraper construction.

Source: CC BY-SA 3.0

It opened with great celebration – with Ohrstrom boastfully laying claim to the title of “the world’s tallest,” while in blissful ignorance of the final trick Chrysler had yet to pull from his sleeve.

Replacing the original plans of a dome shaped roof, Van Alen enhanced the design with the addition of an iconic 186 foot spire, which was hoisted to the top of the structure in secret and assembled in a mere 90 minutes.

Source: CC BY-SA 3.0

This raised the building’s height to 1,046 feet, a total of 77 floors - allowing Chrysler, less than one month later to trump Ohrstrom’s record.

The battle continued long after both blocks were completed, with the consulting architects of 40 Wall Street, Shreve & Lamb, writing a newspaper article claiming that their building contained the highest useable floor and was therefore more deserving of the title.

The Empire State Building however, was to settle the matter.

Hamilton Weber the original rental manager, takes up the story.

“We thought we would be the tallest at 80 stories. Then the Chrysler went higher, so we lifted the Empire State to 85 stories, but only four feet taller than the Chrysler. Raskob was worried that Walter Chrysler would pull a trick - like hiding a rod in the spire and then sticking it up at the last minute,” Weber is quoted as saying in The Empire State Building Book by Jonathan Goldman.

The solution to Raskob’s worries was to add what he quaintly termed “a hat!" - marketed as a mooring mast for dirigibles - although never utilised due to the strong winds and updrafts that circulated at the top.

This raised the building’s height to 1,250 feet, easily outstripping both Chrysler’s and Ohrstrom’s efforts, allowing Raskob to scoop the title.

Taking just 13 months to complete, 58 tons of steel, 60 miles of water pipe, 17 million feet of telephone cable and appliances to burn enough electricity to power the New York city of Albany. The Empire State building with 2.1 million square feet of rentable space opened on 1 May 1931 empty - just as the country was entering one of the worst economic depressions in recorded history.

Source: CC BY-SA 3.0

Dubbed ‘The Empty State Building’ – it did not turn over a profit until 1950 putting Raskob, who in 1929 had penned the famous article Everybody Ought to be Rich by investing in “America’s booming corporate economy”, deep in the red.

Article continues on the next page. Please click below.

The history of this era is a fascinating study. However as entertaining as the story is, it does not stand in isolation.

From long before the Empire State Building was completed, to the most recent example - the Burj Khalifa in Dubai - mankind’s quest to reach the heavens and demonstrate power through the imposing dominance of ‘the world’s tallest’ structure has - with no notable exception - commenced at the peak of each real estate cycle and opened its doors during the bust.

The pattern is easy to follow:

Improvements in the economy are first reflected in rents, which adjust quicker to market conditions than associated expenses - insurance and utility rates for example – which are subject to contract and therefore typically rise out of step.

This in turn attracts speculative investment, pushing prices upwards beyond the cost of replacement, fuelling a cyclical rise in construction - usually for the purpose of speculation, rather than genuine home buyer demand.

The steeper land values become, the higher the building must be in order to achieve a profitable return, this in turn increases demand to concentrate both labour and capital around what is usually a centralised core.

There is however a lag in the time it takes for high-density construction to reach the market – usually a number of years – before the extra supply can drive down both rents and values, resulting in the building boom outlasting the boom in prices, and an overhang of vacancies when the fervour dissipates.

Notwithstanding, there are limits to how high you can extend before the whole project becomes unprofitable.

William Mitchell, dean of the School of Architecture and Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, makes the following point in his 2005 publication Placing Words Symbols, Space, and the City:

“… floor and wind loads, people, water and supplies must be transferred to and from the ground, so the higher you go, the more of the floor area must be occupied by structural supports, elevators and service ducts. At some point it becomes uneconomical to add additional floors, the diminishing increment of useable floor area, does not justify the additional cost.”

In a subsequent publication he goes one-step further.

“I suspect you would find that going for the title of ‘tallest’ is a pretty good indicator of CEO and corporate hubris. I would look not only at ‘tallest in the world,’ but also more locally—tallest in the nation, the state, or the city. And I’d also watch out for conspicuously tall buildings in locations where the densities and land values do not justify it”.

Mitchell’s warning to look for the “tallest” is not to be taken lightly.

- The New York Tribune Building for example, one of the world’s first skyscrapers boasting to be "the highest building on Manhattan Island" – opened in 1874 and coincided with the 1873 financial crisis in both Europe and North America.

- The Manhattan Building in Chicago Illinois and the Pulitzer Building in New York, boasting the title of “the world’s tallest” - opened between 1890 and 1891 and coincided with one of the worst economic depressions of that time (particularly in Australia.)

- The Singer Building and The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower in New York, boasting the title of "the world’s tallest" - opened in 1908 and 1909 respectively and coincided with stock market panic of 1907 (the Knickerbocker Crisis.)

- The World Trade Centre in New York, boasting the title of "the tallest twin towers in the world" - opened in 1973 and coincided with the 1973-75 economic recession.

- The Sears (or Willis) Tower, boasting the title of ’the world's tallest" - opened in May 1973, coinciding once again, with the 1973-75 recession.

- The Petronas Towers in Malay – surpassing The World Trade Centre as "the tallest twin towers in the world" - opened its doors to tenants in 1997, coinciding with the Asian financial crisis.

- The Taipai 101 in China, the first to exceed half a kilometre, boasting the title of "the world's tallest" - opened in the early 2000s, coinciding with the ‘Dot.com’ bubble and burst.

- And most recently, the Borj Khlifa in Dubai, the current “tallest in the world’ -, opened in 2009, coinciding the sub-prime crisis, estimated to be the worst economic disasters to date.

Source: Wikipedia

There are numerous examples and rarely do these structures go up alone.

As we are seeing currently both here and abroad, the rate of highrise construction stands at unprecedented levels – funded by low interest rates and a wash of easy credit.

Matthew Guy, Minister for Planning in Victoria, has been a staunch supporter of higher density dwellings, but the risks surrounding a boom on the scale we are witnessing presently, cannot be diminished.

The small one and two bedroom apartments, funded in main by offshore speculation, are poorly designed, lack natural light, do not offer value for money, and lay out the reach of most first home buyers who face tighter lending restrictions for dwellings of this type.

Notwithstanding, Prosper Australia’s Speculative Vacancies report for Melbourne in 2013, revealed many of these properties sit empty – up to 22% in the Southbank and Docklands area – a figure that could well be higher today, considering the rate of what can only be termed, ‘bubble’ construction.

And to make matters worst, there is growing evidence the approved sites for skyscraper construction are being ‘flipped’ prior to commencement, with new owners reapplying to have height limits extended still further.

Developers 'flipping' projects for huge profits – The AGE 1 September, 2014

The next ‘world’s tallest’ will be the proposed Azerbaijan Tower in Baku, due for completion in 2019 – and projected to be 1 kilometre high.

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

It coincides nicely with the completion of ‘the tallest’ residential tower in the Southern Hemisphere - Australia 108 in Melbourne - which at 319 metres tall, will exceed the height of the current record holder - the Eureka Tower - and unless we see changes to current policy will mark another period of financial instability.

Only by removing the accelerants that produce this behaviour – contained in our tax, supply, regulatory and monetary policies – can we start to address the boom and bust cycles that lay us open to economic instability, fuelling the boastful passions of financiers at the expense of the rest of the population.

It is these policies that keep us locked around a centralised core, increasing the cost of land at the margin and resulting in decades of dead weight taxes on every worker in the country being clawed back by way of preferential tax treatment for those that speculate on the rising value of land.

Every citizen in Australia would be richer by a significant margin if we collected instead, the economic rent from land, resources, banking profits, government granted licences and so forth, and used these to fund society’s needs rather than progressively taxing productivity to feed an elevated level of rent seeking behaviour.

But until such a time there is only one moral to this story.

Pride comes before a fall.