Environmental destruction is a war crime, but it’s almost impossible to fall foul of the laws: Shireen Daft

GUEST OBSERVATION

It was defoliants, seen above during Operation Ranch Hand in the Vietnam War, that prompted action to protect the environment during conflicts. (Source: National Museum of the US Air Force)

An open letter from 24 scientists published in Nature last month calls on governments to draft a new Geneva Convention dedicated to protecting the environment during armed conflict.

This inspired a number of headlines that misleadingly said the scientists want environmental destruction to be made a war crime.

But environmental destruction is already recognised as a war crime by the International Criminal Court. The existing legal framework governing armed conflict also provides some protections for the environment.

The problem is these protections are inadequate, inconsistent, unclear, and most military behaviour won’t fall foul of these laws.

The legal protections already in place

There are currently four Geneva Conventions and three Additional Protocols that are supposed to regulate conduct during armed conflict, sometimes known as the rules of war.

The original four Geneva Conventions, which celebrate their 70th anniversary this year, contain no explicit mention of the natural environment.

The use of Agent Orange (and Agents White and Blue) to defoliate huge spans of land during the Vietnam War led to the introduction of the first specific protections for the environment during armed conflict.

It’s shaky video to begin with but 18 seconds in you see US soldiers spraying Agent Orange during the Vietnam War.

Following the Vietnam War, two major developments in the law occurred.

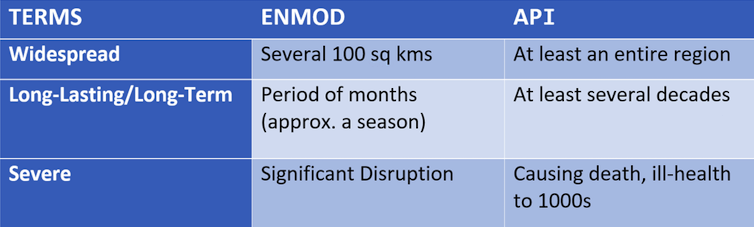

The first was the adoption of the United Nation’s Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques Convention (ENMOD) that prohibits the hostile use of environment-altering techniques that have “widespread, long-lasting, or severe effects”.

The second was the inclusion of provisions in Additional Protocol I (API) that prohibits methods or means intended or expected to cause “widespread, long term, and severe damage to the natural environment” during warfare.

Near impossibly high standards

Both treaties set a very high threshold for falling foul of the prohibitions. API requires that all three elements of damage — widespread, long term, and severe — must be met for military action to be in violation of this provision.

The consequence is that most military behaviour, even when damaging the environment, won’t be in violation of these laws.

Making it even more difficult, the meaning of the three terms differs between the two, and there is ongoing disagreement as to their definition.

While an understanding was reached to determine the definitions in ENMOD, there is still dispute about the meaning of the terms in API. The definitions provided here are among the more commonly accepted. Shireen Daft, Author provided

The only environmental destruction in recent times that has been considered to meet such a high threshold was the setting alight of Kuwaiti oil fields by Iraqi forces as they withdrew during the 1991 Gulf War.

A Kuwaiti oil well fire, south of Kuwait City, in March 1991. Wikimedia/EdJF, CC BY

The United Nations Compensation Commission held Iraq liable for the environmental damage caused in Kuwait. But because Iraq was not a party to either ENMOD or API, the Commission applied a unique legal standard derived from Security Council Resolution 687 and Iraq is still paying compensation to Kuwait to this day.

Neither ENMOD nor API specifies that a breach of these provisions constitutes a war crime. This came in 2002 when the Rome Statute establishing the International Criminal Court came into force.

The Rome Statute says it is a war crime to intentionally cause “widespread, long-term, and severe damage to the natural environment which would be clearly excessive” to the military advantage to be obtained.

The terms are not defined in the Rome Statute, and what is meant by “clearly excessive” is subjective, and introduces a test of proportionality.

Another Geneva Convention?

A new international agreement that balances the interests of environmental protection and respects the laws on armed conflict could be of enormous benefit.

The existing legal framework is only equipped to deal with direct attacks on the natural environment.

But this ignores the many other ways the environment is affected by conflict. Resources such as diamonds, coltan, timber and ivory are all used to help fund conflicts, and this can place enormous stress on the environment.

A particular gap is that no consideration is given in the existing framework to non-human species - to wildlife affected by war or to animals used for military purposes. Yet conflict has proved the biggest predictor of population declines in wild species.

But a new treaty that creates strong, effective, and enforceable protections requires significant political will.

An attempt was made two decades ago, headed by Greenpeace, but no agreement could be reached. That attempt was made during a time when international cooperation and treaty development was at its highest, following the end of the Cold War.

In the current political and social environment it seems unlikely any attempt for such an agreement would be successful. At best, we would see watered-down protections, no stronger than what is already in place. Thus drafting such a Convention now could do more harm than good, in the long run.

If not a new treaty, then what?

The International Law Commission (ILC) is about to release its report dealing with the issue of protecting the environment during armed conflict. This was what inspired the Open Letter from the scientists in the first place.

The Draft Principles it is producing are not new principles of law, but those already found in the existing legal framework. Unfortunately the work produced so far continues to use “widespread, long term, and severe” with no clarity as to what they mean.

But they do confirm that all the fundamental principles of the rules of war apply to the environment, and should be interpreted “with a view to its protection”. The environment should not be a target, and the impact on the environment must be taken into consideration in military operations.

The work of the ILC should inform governments of the interpretation of existing law. Governments should then give more attention to the environment in the operational guidelines used by their militaries.

The Australian Law of Armed Conflict manual, used by our defence forces, already acknowledges they have a duty to protect the natural environment. The next step is to move beyond this general principle to the specific, and have clear guidelines about what protecting the environment during armed conflict means, in practice.

The International Committee of the Red Cross is also currently updating its guidelines for all military manuals to ensure the environment is a consideration to be evaluated during all military operations.

While the world might not yet be ready to consider a new Geneva Convention relating to the environment, the survival of our natural environment does depend on changes being made to the way the war is conducted.![]()

Shireen Daft, Lecturer, Macquarie Law School, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.